Briefing: Iran Protests

Is Iran on the brink of revolution?

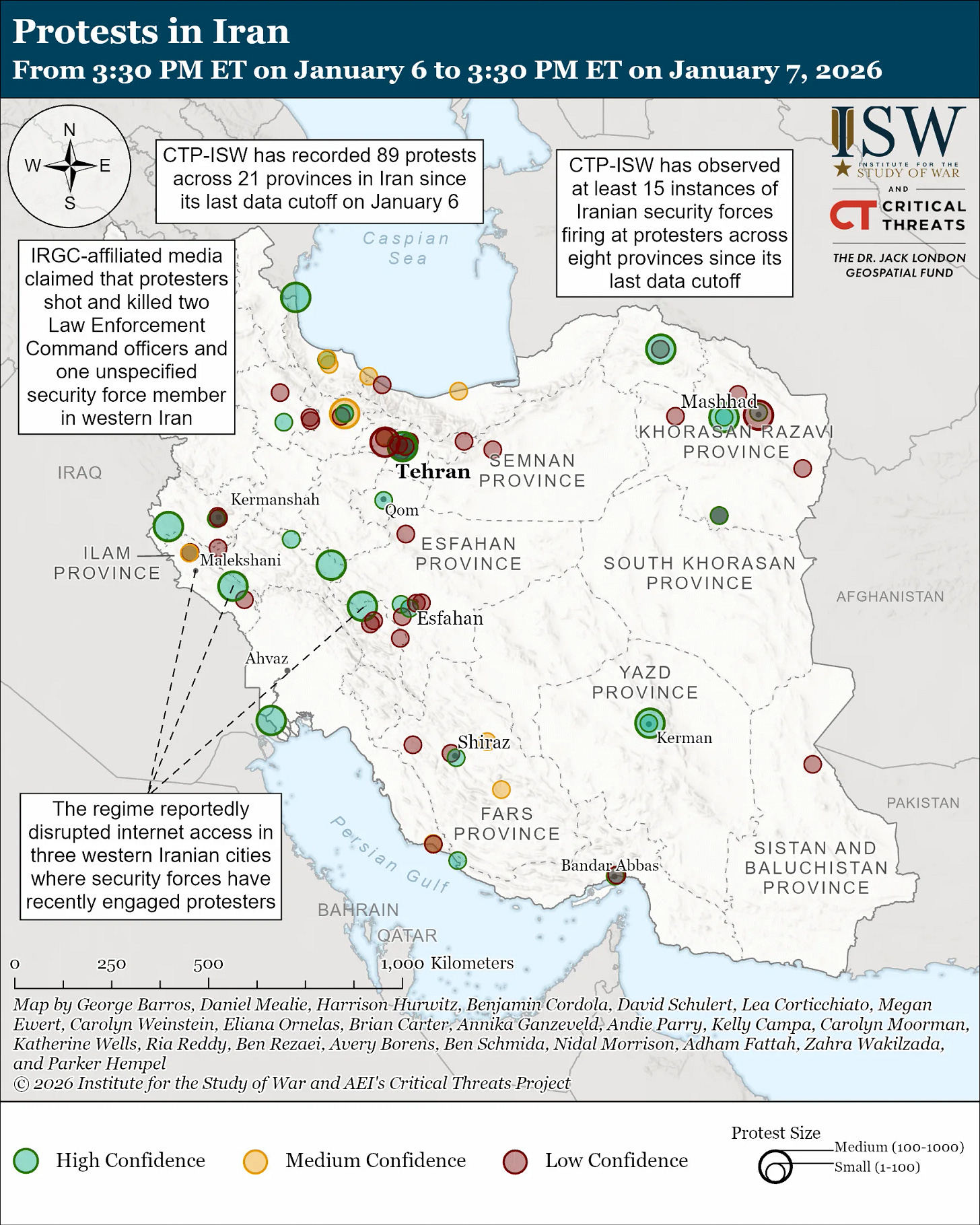

On December 19th, the Iranian government introduced a new pricing tier for gasoline (Iran heavily subsidizes the price of gasoline for the public).1 The last time the Iranian government hiked prices in 2019, it sparked nationwide protests and a subsequent violent security crackdown in which hundreds died. It took nine days for history to repeat itself: Protests in Tehran broke out in December 28th after the Iranian rial plunged to a record low of 1.42 million to the dollar, and the following day unrest spread to other major cities including Isfahan, Shiraz, and Mashhad. Neither the rial’s collapse nor the unrest have abated.

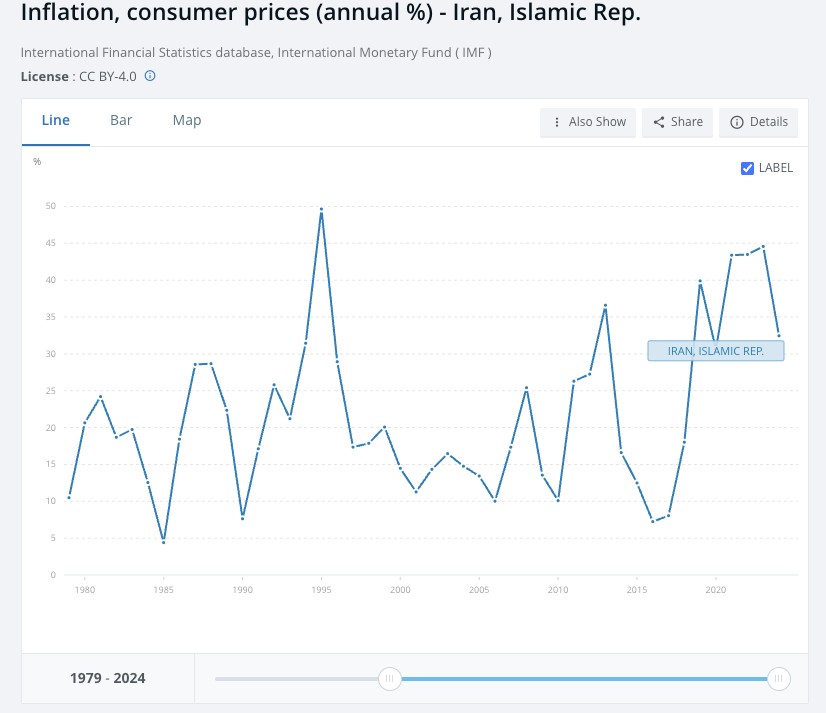

Central Bank Governor Mohammad Reza Farzin’s resignation on December 29th did nothing to quell the protests. Attempts by the Iranian government to strengthen the rial have failed; its value dropped to a new record low of 1.5 million to the dollar on January 5th. A plan to distribute cash handouts to every Iranian citizen risks exacerbating the currency decline it is meant to offset.2 There are no easy or obvious policy steps the Iranian government can take to halt the economic collapse. It is also worth noting that the collapse of the Iranian rial is the culmination of months of pressure: inflation in Iran has been above 40 percent for months.

U.S. President Donald Trump’s first reaction to the protests was stark: He posted on social media on Jan 2nd that, “If Iran shots and violently kills peaceful protesters, which is their custom, the United States of America will come to their rescue. We are locked and loaded and ready to go. Thank you for your attention to this matter!”3 He has been slightly more circumspect in recent days, balancing comments in defense of Iranian protesters with a reticence toward getting involved: “I think that we should let everybody go out there and see who emerges.”4

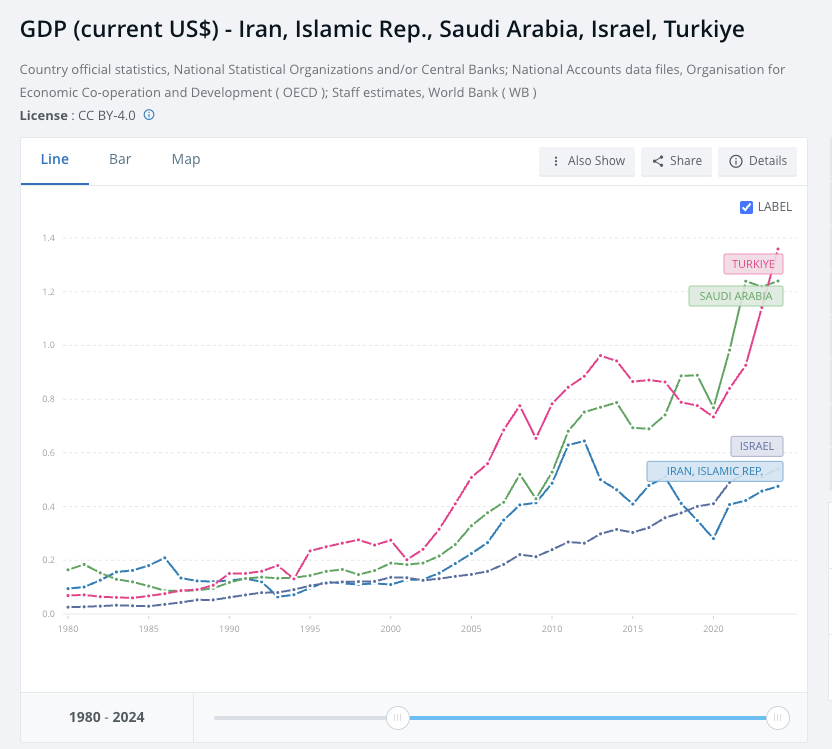

Iran is no stranger to economic pressure, as the 2019 protests attest. When the current regime took over in 1979, Iran had one of the largest GDPs in the Middle East. For a brief period in the 1980s, Iran’s economy was larger than Saudi Arabia, Turkey, or Israel’s. Since the 1990s, however, a combination of economic mismanagement and sanctions have caused the Iranian economy to suffer relative to the other major economies in the region (and relative to the immense resource wealth and human capital Iran possesses).

Sanctions have been in place for years, so the rial’s sudden collapse isn’t about a new restriction or even low oil prices. It’s about a break in expectations. For a long time, the currency was propped up by the hope of relief: a revived nuclear deal, partial sanctions easing, or policy change in Washington. That hope has evidently evaporated. Once people conclude that no deal is coming, demand for rials collapses as households, firms, and elites rush into dollars, gold, and hard assets. At the same time, Iran’s usable foreign exchange is thinner than it looks. Even as oil exports continue, revenues are heavily discounted, often trapped abroad, or paid in illiquid currencies, leaving the central bank unable to defend the exchange rate.

Low oil prices matter, but mostly as an accelerant rather than the root cause. Lower prices hit Iran harder than most producers because it can’t borrow, hedge, or attract capital to smooth revenue shocks, forcing greater reliance on money printing to fund rising security costs and subsidies. That feeds inflation and further weakens the currency.

The deeper problem, however, is political: succession uncertainty (Ali Khamenei is 87 and ailing, and more important has created controversy by attempting to position his son as a successor…getting rid of hereditary rule was one of the key reasons for getting rid of the Shah), recurring protests, and policy paralysis have convinced more and more Iranians that reform is off the table. Currencies can crash for myriad reasons, but in this case, the crash of the Iranian rial suggests the people believe things are not going to get better.

Indeed, the current protest wave is different than recent protests (2009, 2019, 2022) in how squarely focused they are on the economy. That was one of the hallmarks of the 1979 protests that brought the Shah down and the current regime to power. Merchant closures, strikes, and market disruptions have in many cases preceded large street demonstrations. The protests have assumed a life of their own, but their genesis was not a spontaneous expressions of anger. They signal that a constituency long viewed as regime-adjacent is either unwilling or unable to absorb further economic pain. When bazaars shut down, it’s not just protest, it’s a warning that a key stabilizing pillar of the system is cracking, and that repression alone can’t force confidence or normal economic activity back into existence.

Even if this round of protests is eventually contained, the underlying problem hasn’t changed: the Islamic Republic no longer has a credible economic or diplomatic off-ramp.5 Sanctions continue to choke revenue and access to markets, corruption and governance failures blunt domestic policy responses, and there is no realistic prospect of near-term relief from abroad. To paraphrase Hamidreza Azizi, repression can buy time, but it can’t stabilize the currency, restore purchasing power, or persuade people that things are about to get better. The state is managing symptoms, not causes, and that virtually guarantees the unrest will return, even if this particular wave fades for now, unless a radical new policy direction is pursued once the unrest is quelled.

To add insult to injury, this economic collapse comes less than a year after Iran was humiliated in a brief and ultimately one-sided war with Israel. What was the point of the decades of inflation and sanctions and international isolation if Iran does not have a security force capable of defending the country or a nuclear deterrent capable of preventing Israel, the U.S., or anyone else from attacking Iran directly?

Kamran Bokhari, a former colleague, wrote about the protests for Geopolitical Futures, and this was the key point: “Protests alone do not usually bring down regimes. What does collapse regimes is security forces refusing to carry out the political leadership’s orders in the face of overwhelming popular resistance. In the case of Iran, the fragmented nature of the security establishment and its pervasive role in decision-making complicate this picture.”6 The key thing to watch for going forward is whether the regime blinks. There is plenty of speculation that is already happening — from the irresponsible (and ultimately untrue) reports that the Supreme Leader is planning to decamp to Moscow, to more measured accounts of the Supreme Leader’s replacement by “a de facto leadership council composed of the president, the speaker of parliament, the head of the judiciary, and senior representatives from the IRGC and the regular army.”7

That has several analysts fantasizing theorizing that a Maduro-style scapegoating strategy is possible. This “collective leadership” might seek to offer Khamenei up to the U.S., in return for some combination of sanctions relief, inviting U.S. oil companies to Iran, and anything else that might stabilize the economy while preserving the system. It will be harder for that to happen in Iran than Venezuela: Maduro took over for Hugo Chavez, an ideological figure to be sure, but not a revolutionary theocratic one like the Supreme Leader. Whether the IRGC, which is supposed to safeguard the revolution, can survive the hypocrisy of betraying the Supreme Leader in the name of preserving the revolution, remains to be seen. There are also other figures emerging that may sense opportunity — former pragmatist president, IRGC rival, and JCPOA architect Hassan Rouhani has been more vocal lately.8 The son of the Shah is indulging in delusions of grandeur that he might serve as a “steward of a national transition to democracy.”9 Hope springs eternal.

The consensus view is that Iran may not be on the verge of imminent collapse, but it is drifting into a far more dangerous zone, one where economic failure, political paralysis, and elite fragmentation begin to reinforce each other, aka the times they are a-changin.10 But this is the point where I am forced to remind you that this is the 3rd time in the last 10 years Iran has faced significant protests. The previous two times, there was breathless anticipation of major change, but nothing happened. If I had a nickel for every time I’ve heard that the Supreme Leader was sick or about to be replaced in the last 10 years I’d have a lot of nickels. Ultimately, the regime has always retained its monopoly on force.

There is also a vocal and influential Iranian diaspora that magnifies political dissent in Iran; Israel also has a powerful incentive to hype any political upheaval in Iran. Iran is still an authoritarian state, and the quality of the information we can get out of Iran is suspect, even more so with the recent shutdown in the Iranian internet.

Which is precisely what make the protests in Iran is a classic analytical trap. Everything that has happened in the last 10 years suggests this bout of unrest will be settled like all the others...but that complacency might lead an analyst to dismiss that perhaps this time is different. I’ve been very cautious about having a take here, and the recent shutting down Iranian internet makes me even more nervous because what little information we were getting is now gone. I confess I’m starting to move cautiously in the direction of this being different than previous episodes, but I also think Kamran is right: The regime’s survival now hinges less on suppressing protesters than on whether its own power centers believe the system is still worth defending. History suggests that regimes don’t fall when people protest; they fall when insiders decide the costs of obedience exceed the benefits.

Iran hasn’t reached that point yet. The rial’s collapse, the bazaar closures, the sanctions pressure pushed by the Trump administration, the rumors of quiet maneuvering, all coming in the context of the embarrassing defeat by Israel last year — these are potential signs that things might be different this time around. They might also simply lead to an even more far-reaching and violent crackdown. For now, rumors of the regime’s demise are slightly exaggerated, and President Trump may have the right idea: “I think that we should let everybody go out there and see who emerges.” It is possible to hope for change and be open to the possibility that this time is different without abandoning one’s faculties.

https://apnews.com/article/iran-subsidized-gasoline-price-increase-ec18d69bf4e977fefc9c92b8f8f62215

https://www.iranintl.com/en/202601051193

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/amid-mass-iran-protests-trump-takes-cautious-approach-2026-01-09/

https://geopoliticalfutures.com/iran-elite-paralysis-and-systemic-decay/

https://www.euronews.com/2026/01/08/a-big-storm-is-coming-triggering-major-upheaval-iranian-analyst-tells-euronews

https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2026/01/06/pahlavi-iran-democracy-transition-planning/

The Architecture of a Crisis Manufactured by Hostile Foreign Powers.

An exclusive exposé on the hidden forces, intelligence networks, and propaganda machinery fueling turmoil in Iran.

https://felixabt.substack.com/p/the-architecture-of-a-crisis-manufactured

Everyone’s asking whether Iran’s regime is collapsing or cracking down. Almost no one is asking how these Iran protests are being shaped by sanctions, US–Israel strategy, intelligence agencies, and critical minerals.

Just published a Geopolitics In Plain Sight deep‑dive on the US–Israel regime‑change playbook in Iran’s protests—from fault lines and social media amplification to the lithium and copper race and India’s real position.

If you want more than surface news and actually understand the Iran protests + regime change + critical minerals story, read it here:

https://substack.com/@geopoliticsinplainsight/p-184618400