Greenland

The end of everything or the beginning of nothing?

In my last post, I suggested that Venezuela was an appetizer and that Cuba was the main course. As it turns out, Venezuela might have been the amuse-bouche for this New American Empire. Greenland might be on deck as the appetizer.

On Monday, U.S. President Donald Trump told reporters, “We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security…Let’s talk about Greenland in 20 days.”1 Later that day, Stephen Miller insisted that “the formal position of the US government is that Greenland should be part of the U.S.” and that the U.S. would use force if necessary to take it.2 White House Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt said, “President Trump has made it well known that acquiring Greenland is a national security priority of the United States, and it’s vital to deter our adversaries in the Arctic region.” Someone on Polymarket made a $40,000 bet the U.S. will “acquire” Greenland.3 The only member of the administration to tone down the Greenland rhetoric has been Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who insisted President Trump wanted to buy Greenland, not conquer it, and that his statements were part of a real estate negotiation.4

Denmark’s Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen5 is taking the rhetoric seriously. Speaking to a Danish TV station, she warned that “if United States chooses to attack another NATO country militarily, everything will stop, including NATO and thus the security that has been provided since the end of World War II.”6 In a rare bit of European unity, the leaders of France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, the UK, and Denmark published a joint statement insisting Greenland belongs “to its people…it is for Denmark and Greenland, and them only, to decide on matters concerning Denmark and Greenland.”7 Color President Trump unimpressed. When asked what he thought of Denmark increasing its spending on Arctic security by $13.7 billion last year, he replied, “You know what Denmark did recently to boost security on Greenland? They added one more dog sled.”8 Whatever you think of the man, he can be pretty funny sometimes.

A (very) brief history of Greenland

Greenland is the world’s largest island. Located between Canada and Iceland, it covers an area of more than 2.1 million square kilometers, of which approximately ~80% is under ice.9 Greenland’s population is roughly 57,000. The vast majority are Greenlandic Inuits, descendants of migrants who arrived in the 12th century across the Nares Strait from northern Canada. The first Danish settlement on the island was created in 1721 at what is today Greenland’s capital, Nuuk. In a fun bit of historical irony, in 1776, i.e., the same year the U.S. declared its independence, Denmark solidified its control over Greenland by establishing the Royal Greenland Trading Department (KGH) as a government monopoly, restricting foreign access and assuming full control over trade. The 1814 Treaty of Kiel (part of the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars) saw the division of Denmark-Norway, with Denmark retaining control of Greenland. In 1933, the Permanent Court of International Justice reaffirmed Denmark’s claim to the island over Norway’s.

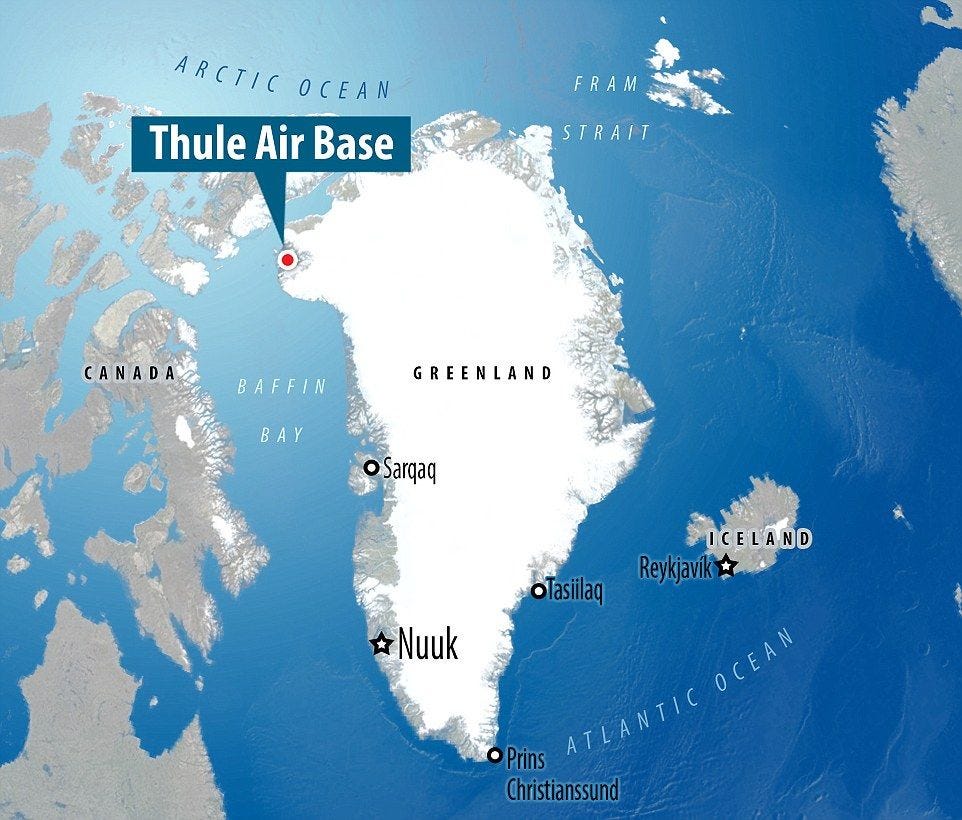

After Nazi Germany occupied Denmark in 1940, Denmark’s control over Greenland was temporarily severed. Due to the island’s critical position related to the allied blockade of Germany, the so-called the Battle of the Atlantic, Denmark agreed to allow the U.S. to establish bases on Greenland, marking the first official U.S. presence on the island. After the war ended, Denmark became a founding member of NATO in 1949, and U.S. military presence on Greenland remained. In 1951, Denmark and the U.S. signed the Greenland Defense Agreement, which allowed the U.S. to establish and operate military bases in Greenland for NATO defense, including Thule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base). Denmark resumed formal control of Greenland in 1953, converting its status from colony to overseas county, but U.S. military presence deepened. The U.S. built towers for military radio communication, used Thule for reconnaissance runs over the Soviet Union, and even tried to build a network of mobile nuclear missile launch sites under the Greenland ice sheet, the idea being they could survive a first strike on the U.S. mainland.”10 Greenland’s importance to the U.S. waned in the years immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but never to the point of withdrawal of U.S. military presence.

Greenland remains part of the Danish Realm but has enjoyed home rule since 1979. Recent polling suggests 56% of Greenlanders would vote for independence if a referendum were held today.11

Why is Greenland important?

Three things make Greenland of strategic importance to the United States. In order of importance, they are:

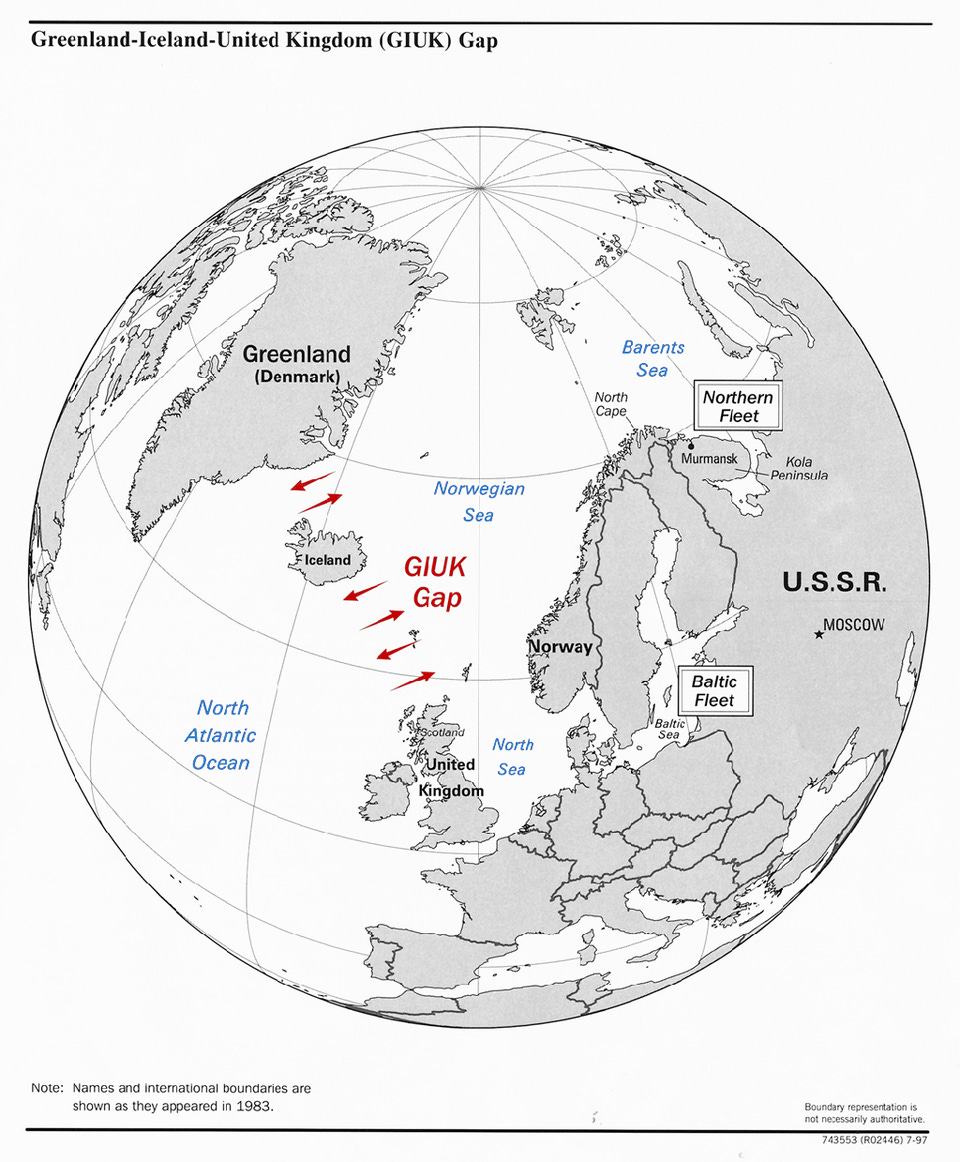

The Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom Gap, aka, the GIUK Gap.

World War II and the Cold War made the GIUK Gap a critical strategic naval chokepoint for the U.S. When WWII broke out in 1939, German ships attempted to break out of the gap from their bases in northern Germany and occupied Norway to attack Allied shipping convoys. Had Germany been successful in blocking U.S. convoys to the UK, the Battle of Britain might have turned out differently.

The Cold War maintained the GIUK Gap’s importance, as it represented the only available outlet to the Atlantic Ocean for Soviet submarines operating from the Kola Peninsula. The U.S. and Britain built their Cold War naval strategy around sealing the GIUK Gap, laying a chain of underwater listening posts across it in the 1950s. This SOSUS sonar network made it extremely difficult for the Soviet Northern Fleet to move submarines into the Atlantic without being detected.12

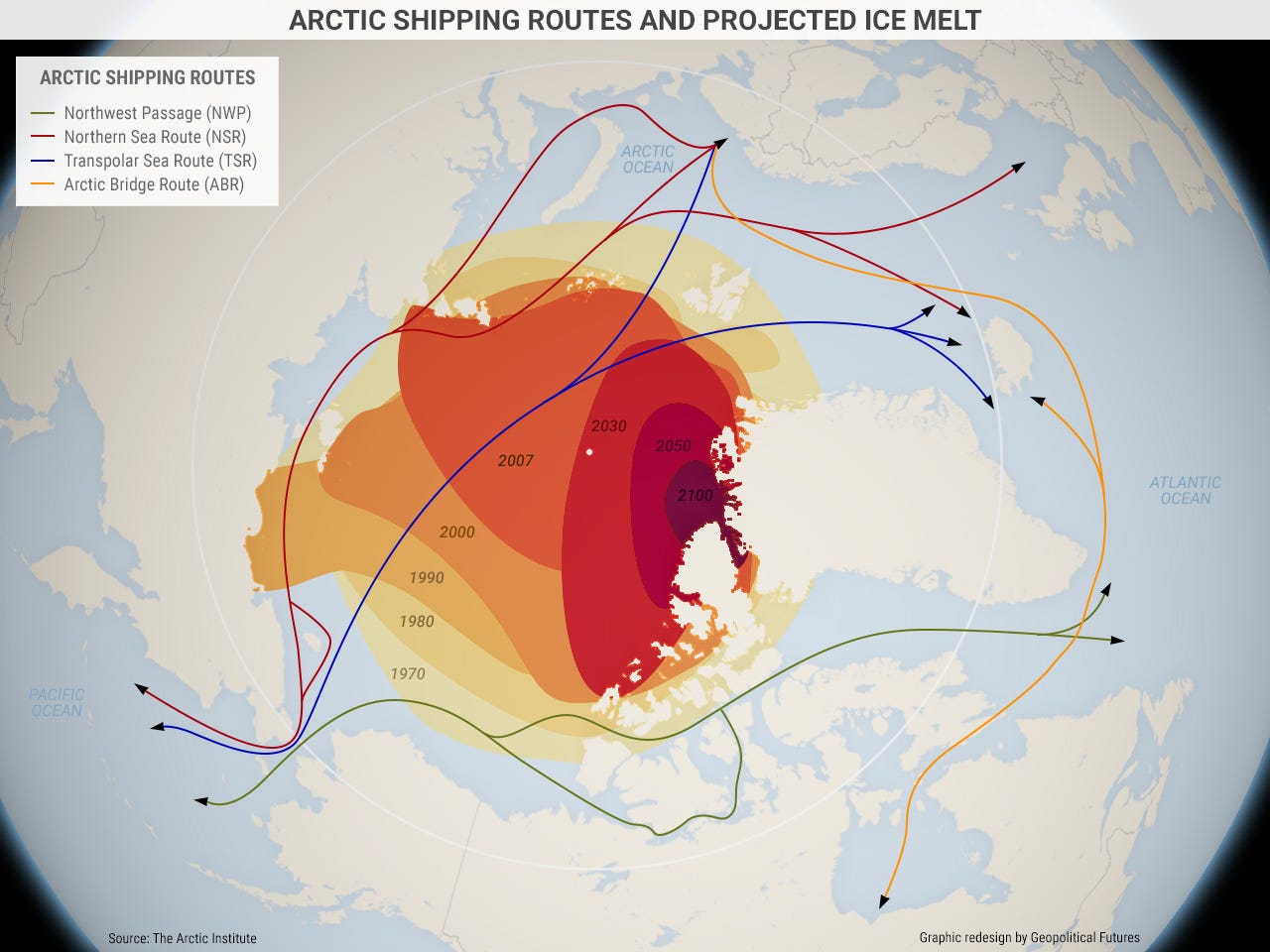

The slow but steady melting of Arctic ice has created new strategic impetus around the GIUK Gap. Currently, these Arctic shipping routes are commercially unviable and will likely remain so for many years because of treacherous weather and floating ice. A 2016 study by the Arctic Institute looked at this issue in detail and concluded that “sea ice will continue to be an integral part of the Arctic Ocean for decades to come and the shipping lanes will be covered in ice throughout most of the year.” Even so, each year, these routes become a bit more feasible, and both Russia and China have focused on the strategic benefits of “polar power”13 — power the U.S. can circumscribe as long as the GIUK Gap is dominated by the U.S.

Pituffik Space Base, formerly Thule Air Base

Pituffik is the northernmost U.S. military installation, sitting on Greenland’s northwest coast. During the Cold War it housed roughly 6,000 U.S. personnel; today that footprint is closer to 150, but its strategic importance has grown in a multipolar world. The base anchors a critical part of America’s missile-warning and space-surveillance architecture, feeding early detection data to North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) and the U.S. Space Force. Pituffik hosts the 12th Space Warning Squadron, which runs a Ballistic Missile Early Warning System designed to detect and track ICBMs aimed at North America, alongside a detachment of the 23rd Space Operations Squadron tied into Space Delta 6’s global satellite control network. Beyond its space and missile mission, the base operates a 10,000-foot runway handling more than 3,000 U.S. and international flights each year and includes the northernmost deep-water port in the world. In an era of renewed great-power competition and Arctic militarization, Pituffik Space Base is less a relic of Cold War geopolitics than a forward outpost for the next one.

Greenland’s resources

Surprised this is the last one on the list? You might think from the breathless14 reporting15 on Greenland’s vast mineral resources that it is awash in treasure of all kind. But Greenland’s largest export, by a considerably wide margin, is cold-water shrimp and fish (especially halibut and cod). Yup. 97% of Greenlands export revenue comes from seafood exports.16 Sure, Greenland has rare earth potential…but rare earths aren’t rare, and rare earths mined from Greenland would still have to be refined in China, which dominates the refining and processing part of the rare earth supply chain. There are some other resources, like zinc and graphite, and the potential for much more, like nickel, copper, and hydrocarbons, but the simple fact is Greenland’s resources are underdeveloped and Greenland has intense restrictions on things like oil exploration and uranium mining. There is nothing from a resource perspective on Greenland the U.S. couldn’t get elsewhere for easier and for cheaper.

One of Greenland’s perhaps most under-appreciated potential resources? Fresh water.17 But that’s a post for another time.

Geopolitics of the Arctic

Greenland’s growing prominence is often explained through a familiar but misleading story: the Arctic is “opening,” new sea lanes will transform global trade, and whoever controls the High North will dominate the future. There is a kernel of truth here. The Arctic is warming, seasonal navigation is becoming more feasible, and geography that once constrained human movement is loosening its grip. But as with most geopolitical myths, the reality is subtler than the headline version.

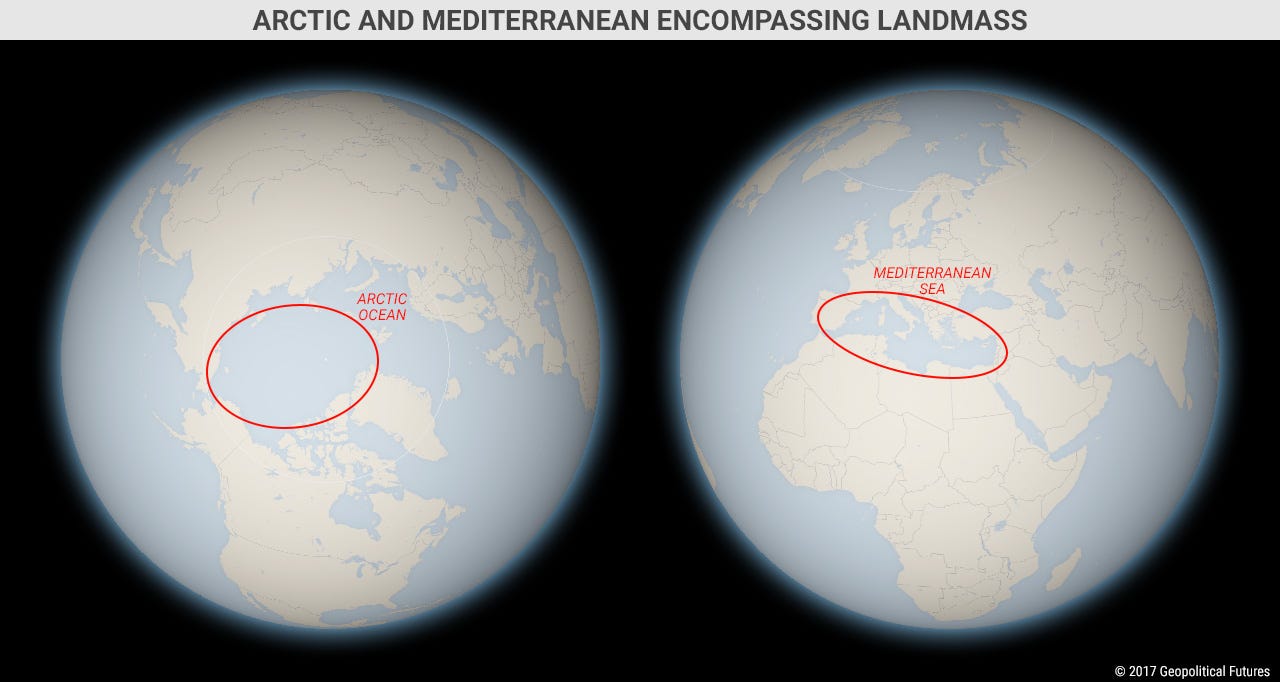

The Arctic is not a new Pacific or Atlantic. It is a small, shallow ocean ringed tightly by land, with states sitting almost on top of one another. In geopolitical terms, it resembles a colder, less populous Mediterranean more than a vast, open maritime highway.18 What matters in such spaces is not domination of the interior, but control of access. This is where Greenland enters the picture.

Much of the excitement around Arctic shipping focuses on distance. Routes that pass north of Greenland can theoretically shorten travel between Europe and Asia or between North America and Asia. But shipping is not governed by straight lines on a map. It is governed by cost, reliability, and insurance. Arctic navigation requires specialized vessels, ice-class hulls, higher operating costs, and acceptance of unpredictable conditions. Even optimistic studies conclude that ice will remain a persistent feature of Arctic waters for decades, making year-round, schedule-reliable trade a distant prospect.

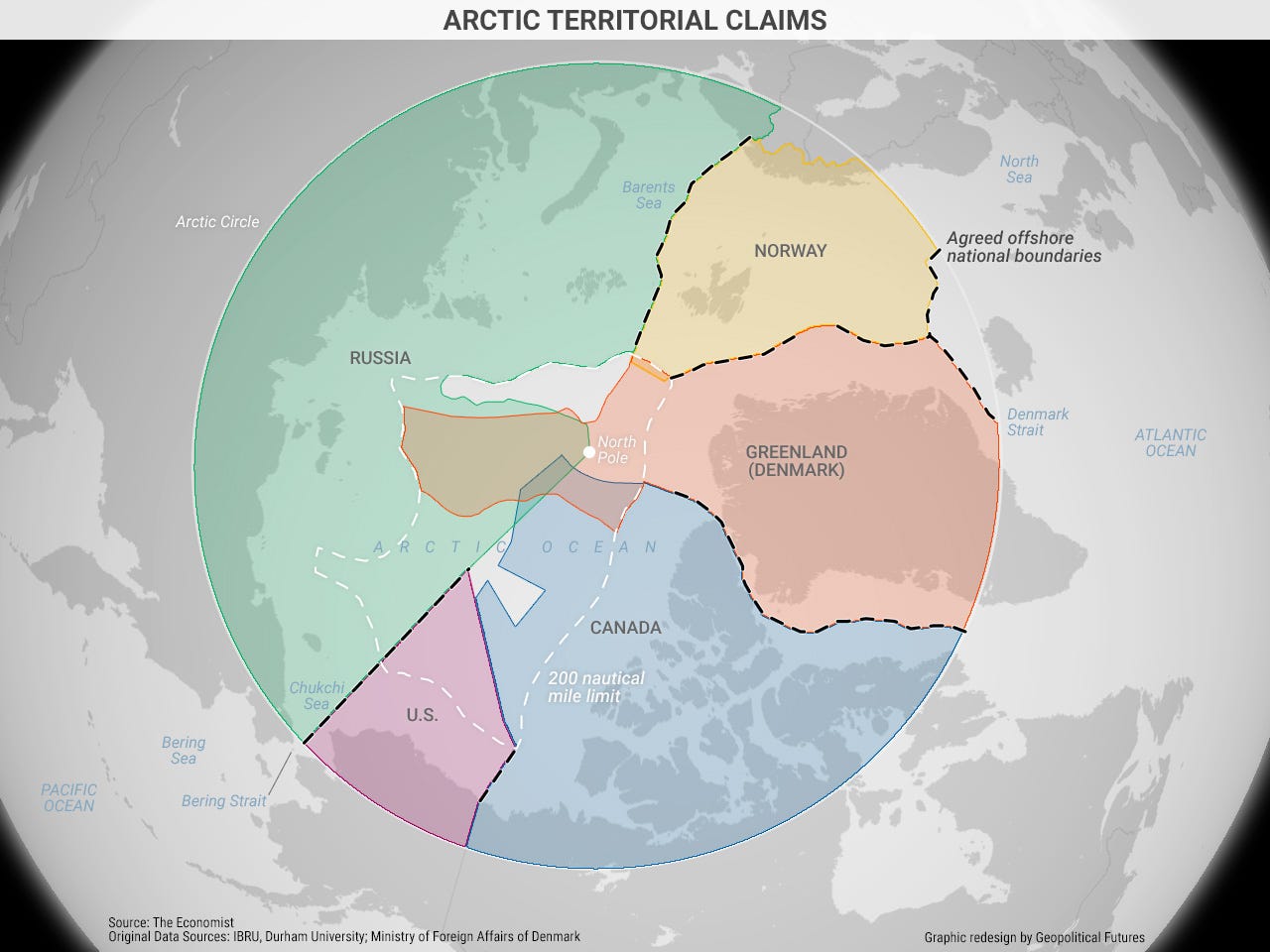

The Arctic is best understood as a containable space. Its key exits — the Bering Strait and the GIUK gap — are natural chokepoints. Russia may hold the largest share of Arctic coastline and the most icebreakers, but geography still works against it. Any Russian movement from the Arctic into the Atlantic or Pacific must pass through narrow corridors dominated or heavily influenced by the United States. China understands this constraint, which is why its “near-Arctic” ambitions emphasize economic access and political influence. The European Union finds itself in an uncomfortable position: formally aligned with U.S., yet facing threats from Washington against the territorial integrity of NATO member Denmark. Without Greenland, the EU has little if any leverage in shaping the future Arctic order.

Greenland’s importance flows directly from this logic. Sitting astride the Atlantic gateway to the Arctic, Greenland is not valuable because it unlocks vast new trade riches or mineral wealth. It is valuable because it anchors the eastern edge of the North American security perimeter. Control over Greenland does not mean control over the Arctic itself; it means influence over who can project power out of it. As ice retreats, Greenland functions not as a prize to be exploited, but as a fixed geographic fact that shapes how power moves between continents.

Precendent19

There is nothing particularly unprecedented about the United States seeking to acquire a piece of strategic territory via threat or purchase. As is usually the case with President Trump, the manner in which he behaves is what is shocking. The impetus to acquire Greenland isn’t. Two of the most obvious examples of similar episodes in U.S. history are instructive in how they are similar and different to President Trump’s posture towards Grenland: the Louisiana Purchase and the Alaska Purchase.

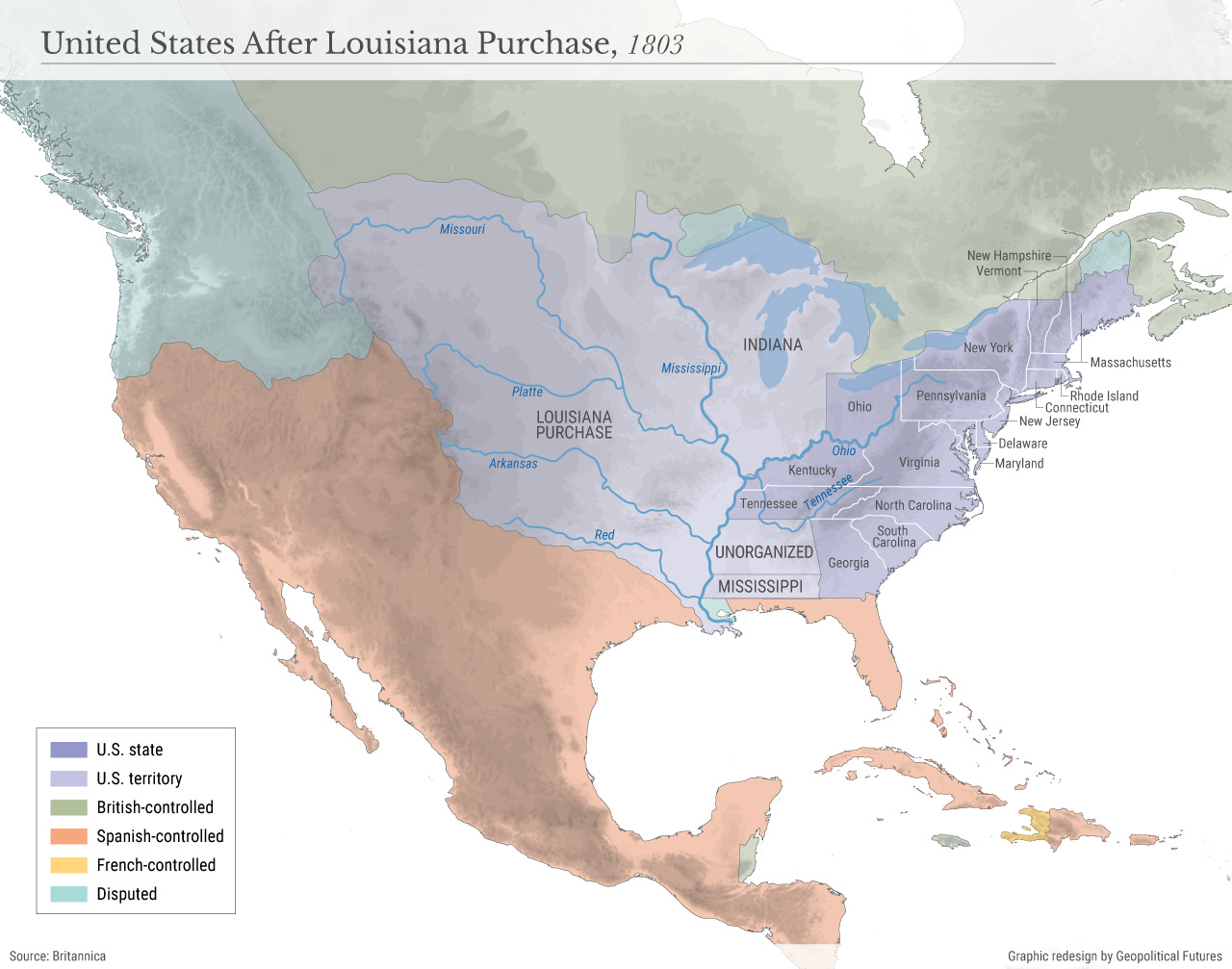

The Louisiana Purchase

Arguably the most significant geopolitical move in U.S. history was the Louisiana Purchase. For $15 million (that’s roughly $450 million in present day dollars),20 the size of the fledgling United Staes was doubled overnight. Not only that, but the U.S. acquired the entirety of the Mississippi River’s drainage basin and the critical Mississippi River port of New Orleans. Then-President Thomas Jefferson had long been eager to acquire Louisiana — and European geopolitics gave him the opportunity to do so.

The Kingdom of France controlled Louisiana from ~1682-1762, at which point Spain took control. In 1800, Napoleon reacquired Louisiana in an effort to reestablish a French colonial empire in North America. Napoleon’s dream was short-lived: He failed to subdue a slave rebellion against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, which we know today as Haiti. This crippled France’s primary logistical base in the Caribbean. In addition, Louisiana was huge and sparsely populated, and Napoleon didn’t stand a chance at preventing Britain’s Royal Navy from seizing it in a war. Ultimately, Napoleon decided to sell it to Jefferson’s special envoys, Robert Livingston and James Monroe. Napoleon got cash to fund new armies and denied the prize from Britain — all for a territory that he determined had become a strategic liability.

The U.S. would have fought a war for control over the Mississippi River eventually — there could be no westward expansion, no manifest destiny, no continental prosperity without control over the world’s largest navigable waterway system. The Mississippi River complex forms a vital economic artery for the U.S. by transporting vast amounts of agricultural and commercial goods, connecting inland ports to global markets via the Gulf of Mexico, and supporting the most productive agricultural region on Earth. Control over the Mississippi was the geopolitical center of gravity for the U.S. in its first century: the 1815 Battle of New Orleans, the defeat of Santa Anna at the Battle of San Jacinto, the Civil War — if any of these episodes had left the Union losing control over New Orleans, the U.S. as we know it today doesn’t exist.

But therein lies the key difference between Greenland today and Louisiana then — the U.S. did not have to threaten France to purchase Louisiana. France wanted to sell it in the first place. President Trump is trying to force Denmark to give up Greenland when Copenhagen doesn’t see that it is in its interest to do so.

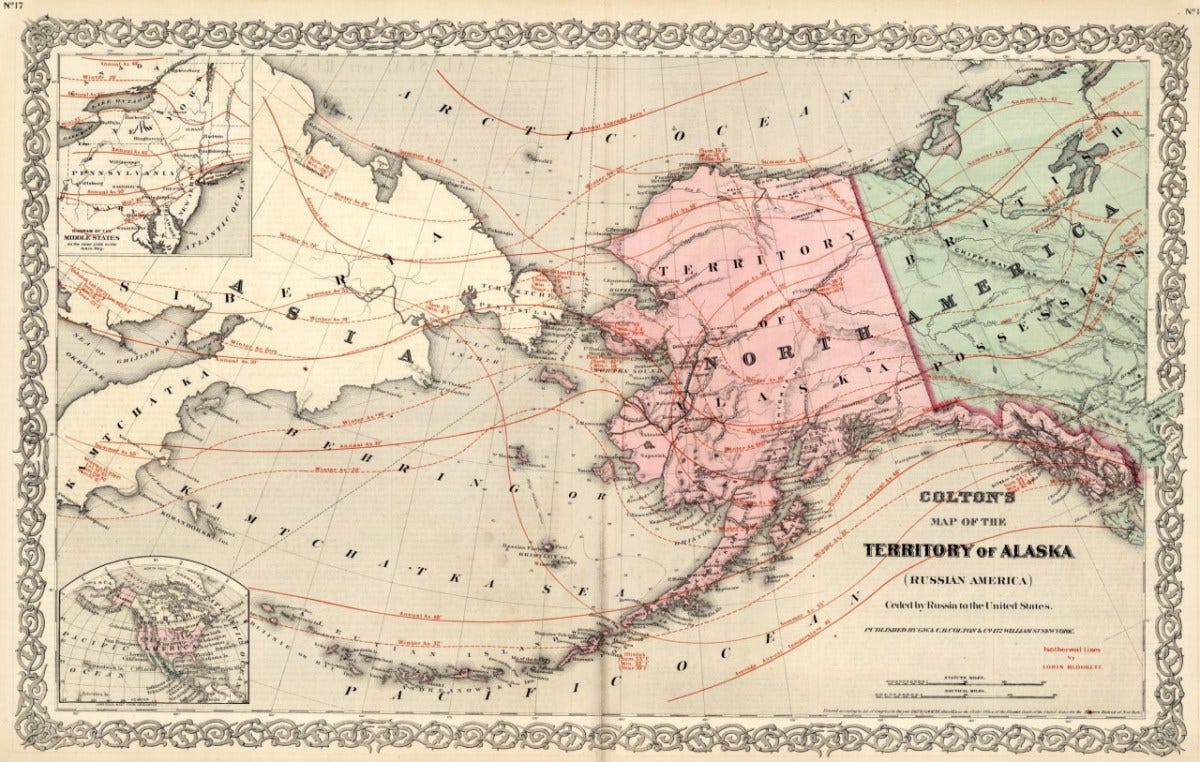

The Alaska Purchase

Another seminal moment in U.S. geopolitical expansion was when the U.S. purchased Alaska from the Russian Empire for $7.2 million (that would be about $135 million in today’s dollars). Alaska was not nearly as critical to U.S. strategy as Louisiana, but it represented an opportunity for the U.S. to acquire a potentially valuable territory for a relatively modest price. As with Napoleon, Russia had delusions of grandeur for a colonial empire in North America, but by the mid-19th century, Russia’s position in North America had become thin and vulnerable, with Alaska sparsely settled and expensive to defend.

Once again European geopolitics intervened, this time in the form of the Crimean War. This isn’t the place to dive deep into the details of that conflict: Suffice to say that Russia was defeated. At the same time, Tsar Alexander the II was busy emancipating the serfs, reforming his army, and building railroads across Russia’s harsh geography. That all required capital the Tsar did not have. Having concluded Alaska was indefensible and would be exceedingly easy for Britain (via Canada) to seize Alaska for itself, Tsar Alexander decided to sell it to the U.S. in 1867.

Unlike with Louisiana, the U.S. might never have looked to acquire Alaska if not for Russia’s position as a distressed seller. There is no innate geopolitical logic that says the U.S. should control Alaska. But as with Louisiana, the U.S. was dealing with an overstretched seller that needed cash urgently, that could not defend its North American territorial possession, and which eagerly wanted to avoid Britain from acquiring that territory for itself.

As with the Louisiana Purchase, the key difference between the Alaska Purchase and a potential Greenland acquisition is Denmark is not an overstretched seller looking to unload a strategically indefensible position to the U.S. to avoid Greenland being taken by a geopolitical rival. Quite the contrary — Denmark wants to keep Greenland. The EU has an interest in remaining an Arctic power. The Trump administration approach to Greenland feels anachronistic because the U.S. is using a 19th century old school imperial playbook in a 21st century system based on the self-determination of nation states, but just because norms have changed doesn’t mean the U.S. attempt to acquire Greenland is strange or unprecedented. To a certain extent, this is about the U.S. finding the semantics to make the acquisition more palatable.

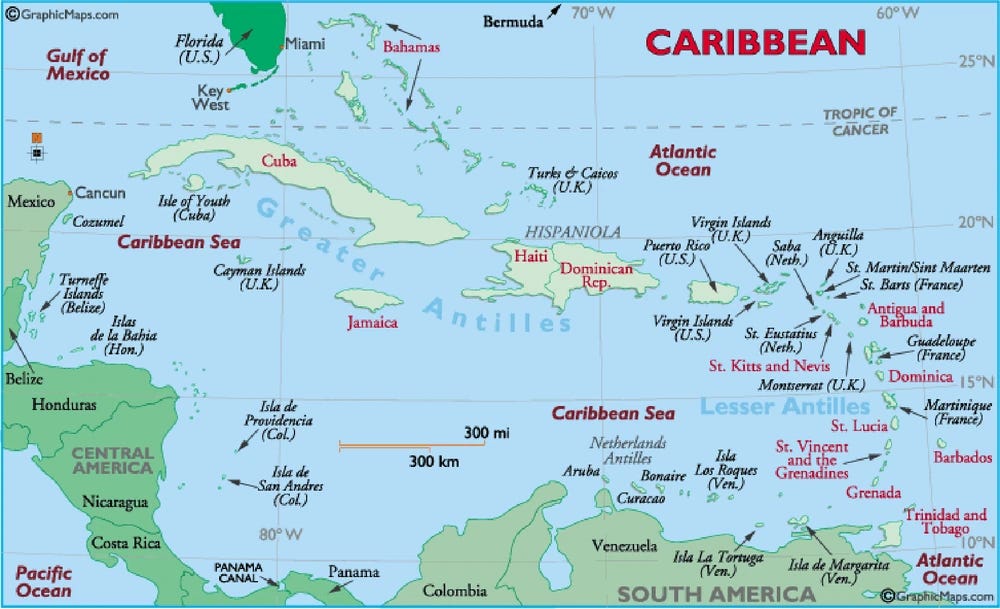

Treaty of the Danish West Indies

Ironically, the best comparison might not be the Louisiana or Alaska purchases, which are admittedly a bit of a stretch. A better comparison might be a previous transaction between Denmark and the United States: the 1916 Treaty of the Danish West Indies. The Danish West Indies were a Danish colony in the Caribbean, consisting of the islands of St Thomas, St John, St Croix, and Water Island. The U.S. government had expressed interest in purchasing the Danish West Indies as early as 1861, when the Union government was eager to acquire a potential Caribbean naval base (the better to block New Orleans). Ultimately, the U.S. and Denmark waited until World War I to make a deal, with St Thomas, St John, and St Croix being purchased in 1916 for $25 million in gold. (The U.S. bought water Island in 1944…today these islands are known as the U.S. Virgin Islands.)

The Treaty of the Danish West Indies offers a cleaner historical analogue for Greenland than either Louisiana or Alaska. The U.S. purchased the formerly Danish islands not because they were economically transformative, but because Denmark could no longer defend them and Washington wanted to deny Germany — or any other European power for that matter — a strategic foothold near the Panama Canal. The logic was less about expansion than about strategic denial under changing security conditions, with a small power trading sovereignty for security guarantees and cash. Donald Trump is being unfair when he claims Denmark has only added a dog sled…but he’s not wrong that Denmark’s overall capacity to secure the GIUK Gap against potential Chinese, Russian, or other threats is lacking.

Stripped of the rhetoric, the Greenland issue becomes a fairly straightforward thought experiment: If this were treated as a deal, what price and structure would actually work for both sides? A former NY fed economist ran that exercise and landed on a wide but instructive range. Using past U.S. territorial purchases as reference points, especially the Danish West Indies, he estimated Greenland could plausibly be valued somewhere between ~$12 billion and $77 billion.21

The logic matters more than the number. Greenland’s value, like the Virgin Islands a century ago, is overwhelmingly strategic rather than commercial: location, access, and denial, not immediate revenue. Attempts to price it based on minerals or hypothetical resource wealth quickly collapse under scrutiny, since the U.S. government wouldn’t capture most of that upside anyway. If Greenland has value, it’s because it enhances U.S. security, and that value scales with the size and power of the American economy, not with commodity prices.

The real leverage in any hypothetical negotiation wouldn’t be cash alone. The United States already guarantees Greenland’s security through NATO, controls key trade access to Denmark’s most important export markets, and has a long-standing military presence on the island. A “deal,” if one ever existed, would almost certainly bundle money, security guarantees, trade concessions, and political face-saving for Copenhagen. Which is precisely why this is less a real estate transaction than a geopolitical stress test, and why even entertaining it publicly has consequences far beyond the price tag.

Constraint #1: What does Greenland want?

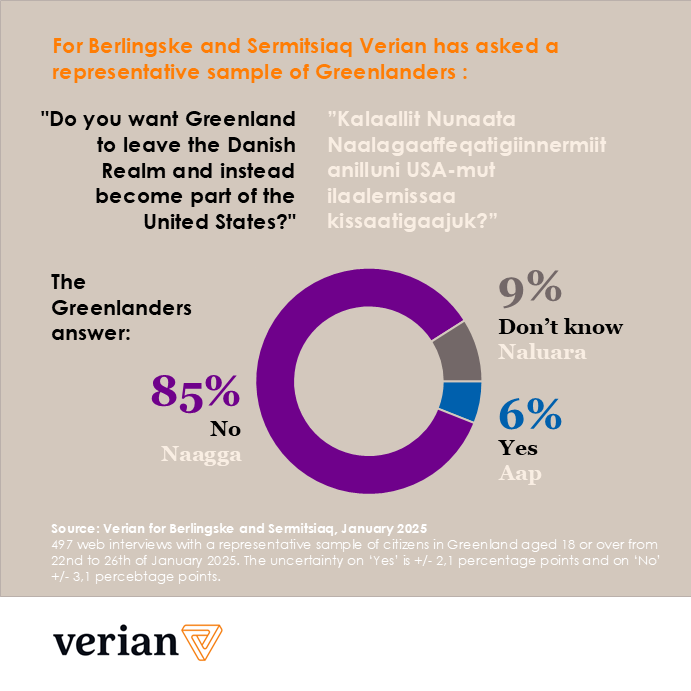

There are key three constraints to the U.S. approach to Greenland that are different from the previous historical analogues I could find in U.S. history. The first is that we do live in the 21st century — imperialism has been discredited, and empires don’t just sell populated lands to each other for purely strategic reasons. Almost 57,000 Greenlanders live in Greenland. The title of their government’s foreign, security, and defense policy 2024-2033 is, “Greenland in the world: Nothing about us without us.” As mentioned earlier, Greenland would likely vote for independence if a referendum was held today. Greenland would definitely not vote to become a part of the United States unless something huge changed. In a January 2025 poll, 85 percent of Greenlanders said “No” to leaving the Danish Realm and becoming part of the United States.

This is not to say the U.S. couldn’t sweeten the pot for Greenland. The U.S. could, for instance, sign a Compact of Free Association, like the ones it currently has in place with Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau. “Under the deals, the U.S. provides essential services, protection, and free trade in exchange for its military operating without restriction on those countries’ territory.”22 This is why the Trump administration’s approach seems to heavy handed. Denmark would likely welcome greater U.S. presence in Greenland. Greenland would love more attention from Washington. The U.S. can get everything it needs and wants out of Greenland without owning it — and yet President Trump continues to declare that his goal is to “make Greenland a part of the U.S.,” and Stephen Miller insists that “nobody is going to fight the U.S. militarily over the future of Greenland.”

Nerd alert: The entire tone of the conversation reminds me of a movie I put on my top geopolitical movie list in a podcast with Cousin Marko earlier this month: Star Trek Insurrection. The basic plot is that a small planet in a rough part of space is the key to immortality — some kind of radiation in the planet’s rings constantly regenerates its inhabitants, which number in the hundreds. The Federation makes a deal with the Son’a to forcibly move the planet’s residents so they can harvest the material in the rings — which will increase lifespans for billions of people but destroy the planet. When Captain Picard realizes what is afoot, he protests to a Starfleet admiral, who claims that they are only moving a few hundred people, so why should it matter. Picard replies with this epic speech:

How many people does it take for it to become wrong for the U.S. to run roughshod over the self-determination of Greenland’s inhabitants? Apparently, for the Trump administration, the number is greater than 57,000. Which is why this isn’t a particularly strong constraint. International law and norms were always somewhat flimsy, but if any one thinks those carry much weight in this multipolar world, they aren’t paying attention to Nagorno-Karabakh, to Gaza, to Cambodia/Thailand, to Russia/Ukraine, to Sudan, to Ethiopia/Eritrea, etc.

Constraint #2: U.S. domestic politics

Let’s say for the sake of argument that Rubio is correct: That Trumps incendiary rhetoric on Greenland is all a negotiating tactic to purchase the island rather than a real threat of military force to conquer it. How much will the Trump administration pony up for the purchase? $100 billion? More? $100 billion isn’t that much money for the wealthiest and most powerful country in the world…but the U.S. also has almost $40 trillion in debt, and the Trump administration campaigned on a platform of ending forever wars and focusing on America First. Just watch Marjorie Taylor Green tear into the Trump administration on its intervention in Venezuela earlier this week on CNN:23

Then again, who can forget in the naive days of 2016, when Trump said shortly before the Iowa caucus that, “I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters, OK?” Bombing Iran doesn’t seem to have hurt Trump in the polls; the polling data on Venezuela suggests 65% of Republicans backed Trump’s military operation. Will Trump lose voters if he starts spending tax dollars to purchase Greenland? (Will he just insist the revenue to purchase Greenland will come from tariffs? Or better yet, from the indefinite control the U.S. energy secretary has declared over Venezuela’s oil sales?)24

The midterms are coming, and Trump’s approval rating on the economy should scare him. But foreign policy is where U.S. presidents get to play when thing aren’t going well domestically, and President Trump is no different than his predecessors in that he is doing exactly that. It does not appear that this constraint will stop the U.S. from moving on Greenland either.

Constraint #3: The End of NATO

Let’s not over-index on the success of the recent U.S. military operation in Venezuela. It is becoming clear that this wasn’t regime change in any meaningful sense: The Venezuelan regime gave Maduro up. It decided Maduro had become a liability and offered him on a silver platter to the Trump administration so that it could stay in power. How else to explain Delcy Rodríguez’s coronation as interim president; how else to explain Trump’s disdain for Nobel Peace Prize winner Maria Corina Machado; how else to explain the U.S.’s ambivalence about Venezuela’s democracy or next election. On the ground, repression has only increased.25

Moreover: the U.S. has faced practically no international consequences for getting rid of Maduro, a man responsible for incalculable death, suffering, and agony. Maduro is a detestable human being, and most Latin American countries support his removal. According to one recent poll, Costa Rica was the most supportive as 87 percent of respondents approved of his arrest, followed by Chile (78 percent), Colombia (77 percent), Panama (76 percent) and Peru (74 percent). Sixty-one percent of respondents in Argentina and 60 percent in Ecuador supported his ouster, as did 52 percent in Uruguay. Only in Mexico did a plurality, rather than a majority, support his arrest. Only 43 percent supported it, with 42 percent opposed.26 The biggest consequence for Trump has been a slap on the wrist from Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum — one wonders how much speaking her conscience on non-interference will cost Mexico in USMCA negotiations.

Going after Greenland would be very different. Operationally it would be easy. But it would have irreparable geopolitical consequences. It is easy to make fun of European nations for lacking a spine — after all, even after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Trump’s second term, the EU is dithering rather than taking robust, rapid, and tough steps to becoming a stronger and more coherent geopolitical power in a multipolar world. But if the United States took Greenland by military force, it would be NATO on NATO action. Mette Frederiksen is not exaggerating when she says it would be the end of NATO. Is the U.S. really willing to blow up the most powerful alliance in modern history, an alliance that played a major role in bringing down the Soviet Union, which might play a major role in containing Chinese power, all for a big rock with 57,000 people, indeterminate resources, and a strategic position the U.S. could control without having to annex the place already controls?

Taking over Greenland would also do nothing to solve much bigger problems for the U.S. — for instance, the continued existence of the Cuban Communist Party and its anti-American dictatorship, the impunity with which drug cartels are acting throughout the Western Hemisphere, spreading their drugs and trafficking and suffering each day, and the economic influence that China has built throughout most of South America, where almost every single country counts Beijing, not Washington, at its largest trading partner. If the U.S. is to rule over a “New American Empire,” if it is to be the dominant hemispheric power in the Western Hemisphere, if it is to prevent countries in the region from sending their commodities to American adversaries…raising the stars and stripes and saying the pledge of allegiance in Nuuk isn’t going to do a heckuva lot to bring that to fruition. The political costs of doing so by force would be enormous.

So, does increased U.S. influence over Greenland make sense? Sure! Far from being unprecedented, this is the way great power politics works. Stronger powers absorb weaker ones that possess a commodity or a position that they want. Big fish eat the little ones. Big fish eat the little ones. But if the U.S. decides that in order to take Greenland, it needs to embark on an unnecessary military operation and a formal annexation of Greenland’s territory, it will be guilty of losing the thing it wants not because it is the wrong strategic goal but by virtue of how it went about achieving it. The U.S. can get what it needs out of Greenland without conquering it; the cost of behaving like its 1899 far outweighs the benefit of adding another star to the American flag.

Considering the constraints, the odds of a U.S. invasion of Greenland seem much lower than the odds seemed a few weeks ago of the U.S. attacking Venezuela or the odds of the U.S. attacking Cuba seem in the coming months. Of course, that doesn’t mean this administration won’t do it anyway. Geopolitical analysts often gets things wrong when they assume the actors they are analyzing see the same constraints they do. But if the U.S. decides to hell with constraints and goes after Greenland with Stephen Miller-style force and aggression, the consequences will be more far-reaching and deleterious to U.S. grand strategy than recent events in Venezuela.

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c4g0zg974v1o

https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/06/us/politics/rubio-trump-greenland.html

High on my global leader trade value index; not so much on Cousin Marko’s.

https://nyheder.tv2.dk/politik/2026-01-06-mette-frederiksen-skaber-overskrifter-i-store-medier

https://www.elysee.fr/en/emmanuel-macron/2026/01/06/joint-statement-on-greenland, emphasis added

https://www.yahoo.com/news/articles/trump-mocks-denmark-increasing-greenland-131809714.html

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/769527/EPRS_BRI(2025)769527_EN.pdf

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Project_Iceworm

https://www.veriangroup.com/news-and-insights/opinion-poll-greenland-2025

https://archive.org/details/stalkingredbeart0000sasg

https://www.swp-berlin.org/10.18449/2025C08/

https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/greenlands-rich-largely-untapped-mineral-resources-2025-01-13/

https://www.brookings.edu/articles/the-greenland-gold-rush-promise-and-pitfalls-of-greenlands-energy-and-mineral-resources/

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2025/769527/EPRS_BRI(2025)769527_EN.pdf

https://www.belfercenter.org/research-analysis/explainer-geopolitical-significance-greenland

https://geopoliticalfutures.com/toward-geopolitics-arctic/

“Unprecedented” is a word that has been thrown around a lot recently in the context of Nicolas Maduro’s recent capture. Democratic House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries described it as “an unprecedented military action.” Experts are describing the last week’s event as “unprecedented.” U.S. legal scholars claim it is an “unprecedented usurpation of [Congress’s] war powers.” Of course, there is nothing unprecedented about it. It is not the first time the U.S. has arrested a Latin American leader (See: Panama, 1989), has deployed military force without Congressional approval (See: Grenada, or Yemen), or upended global norms in pursuit of oil wealth (See: Iran, Iraq).

The word is being used with similar flippancy in relation to President Trump’s Greenland machinations. President Trump’s threats over Greenland are being described as “a new and potentially unprecedented challenge.” Europe’s response to President Trump is similarly being described as “unprecedented.” And yet, there is nothing particularly unprecedented about the U.S. seeking to acquire strategic territory (yes, even from an ally); nothing particularly unprecedented about the U.S. using threats to do so; and nothing particularly unprecedented about a strongly worded statement from a few European nations.

https://www.officialdata.org/us/inflation/1803?amount=15000000

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/11/business/trump-greenland-cost.html

https://www.politico.eu/article/donald-trump-greenland-easy-steps-nato-policy-deal-military/

Is CNN truly so desperate for clicks it needs to have MTG on? This is the same dingbat who thinks there is a Jewish space laser. Now just because she disagrees with Trump she’s worthy of airtime? Fine, keep it up. Just means more people will look to places like this Substack for info than your channel!

https://www.nytimes.com/2026/01/07/world/americas/venezuela-repression.html

https://www.newsweek.com/trumps-capture-of-maduro-is-popular-across-latin-america-new-poll-11318726

Great read. Brief but comprehensive analysis. Thanks for putting this all together. I still think there will come a time post-Trump when we’ll be returning things to an earlier order like an embarrassed mom after her unruly kid has rampaged through the department store.

Fantastic deep dive. The Danish West Indies analogy is way more instructive than Louisiana/Alaska comparisons—it captures the strategic denial logic without the expansion narrative. What I find most compeling is how the GIUK Gap basically makes Greenland a natural geographic veto point rather than an asset to be exploited. During the Cold War we built entire naval doctrine around chokepoint control; now we're debating sovereignty over the chokepoint itself. I worked on Arctic security assessments a few years back and the "Mediterranean not Pacific" framing is spot-on—everyone overstates shipping potential and understates access controll realities.