Meiji 2.0?

Takaichi’s supermajority, the yen constraint, and whether Japan is about to attempt another national reinvention.

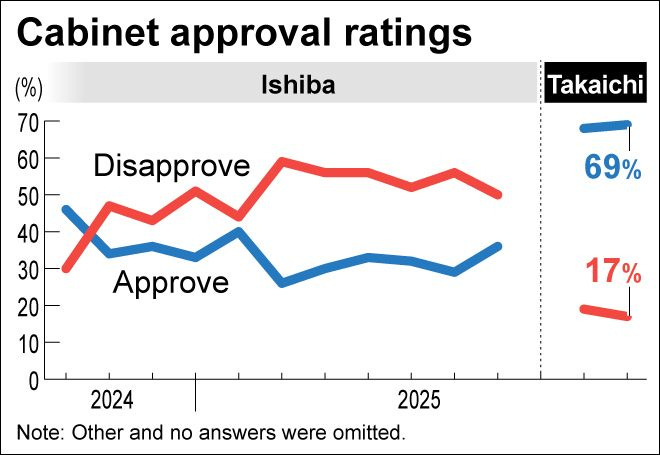

On February 8th, Japan held a general election. The result may be is the most important in the history of modern Japanese democracy. Prime Minister Takaichi Sanae and her Liberal Democratic Party became the first party to secure a two-thirds majority in the House of Representatives, a supermajority that allows it to bypass the upper House of Councillors. The result shocked even the LDP, which literally ran out of candidates for the number of seats it won, forcing it to give 14 seats to rival parties. The only possible critique of the LDP’s victory is that voter turnout was a paltry ~56 percent.1 But that, frankly, is nitpicking. By any other metric, it was an astonishing and total victory for the LDP, and especially for its leader, Takaichi Sanae, who shocked everyone by calling for the election in the first place, and is by far the most popular Japanese leader of her era.2

N.B. I’m not a Japan analyst or expert. If you are looking for one Tobias Harris is one of the best out there writing in English. This is my attempt to overlay a geopolitical analysis onto Japan. It will fall short and generalize in places, but I think it yields a compelling and contrarian narrative to understand the political earthquake we just witnessed in Japanese politics, as well as some key signposts to watch for going forward.

If geopolitics is the study of how constraints shape the actions of nations, Japan is a study in how those constraints don’t always matter. Japan is a country that imports ~60 percent of its food,3 ~90 percent of its energy,4 and most of the raw materials necessary5 to manufacture its goods. Japan is also one of the oldest countries in the world — almost 30 percent of its population is over the age of 65.6 Despite this, Japan has the 4th largest GDP in the world. Despite this, Japan almost conquered Asia in the first half of the 20th century (and if things had gone a little differently at the Battle of Midway,7 maybe would have). It is doubly ironic because most of Japan’s history is rife with domestic infighting and overall instability — but punctuated by brief but overwhelming moments of power, unity, and fierce national pride that enable Japan to rise up and punch far above its weight.8

The question, then, is a deceptively simple one: Is Takaichi’s victory a sign that Japan is rising again? Is Japan about to attempt another reinvention — or is this simply the last confident gesture of a country learning to manage decline? The answer will determine the geopolitics of Asia for a generation.

Takaichi’s victory means the domestic political constraints that hampered her mentor, former Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, are now irrelevant. That is not to say they are non-existent: For one thing, to change Japan’s pacifist constitution, she would need a two-thirds majority in the upper house and a simple majority in a national referendum. For another, Japan’s Finance Ministry in particular will attempt to block her from her ambitious fiscal and monetary goals (my recent podcast episode with Tobias goes deeply into just that topic).9 But Takaichi has the kind of support that allows her to reshape Japan’s institutions if she so chooses. The consensus view on Takaichi is that she is a sort of “Abe 2.0.”10 That reading misunderstands Takaichi’s ambition. If Takaichi becomes Abe 2.0, it means she will have failed in her goals to reinvigorate the Japanese economy and the relationship between the Japanese state and its people. If Takaichi is successful, it will be more appropriate to invoke the era of the Meiji Restoration, a period of explosive growth and strength marked not by a new leader but by a new state that was built quickly under external pressure and which dismantled the old social order and drove rapid institutional change.

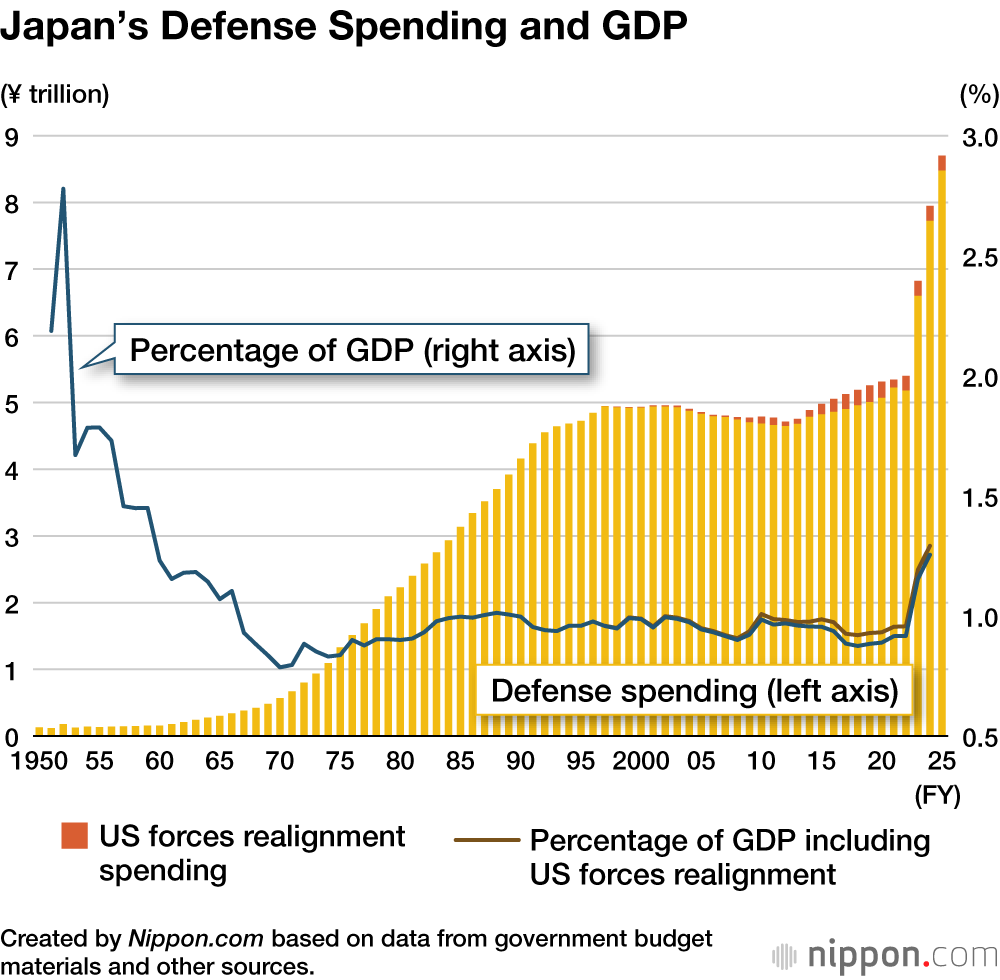

Takaichi wants to rebuild the Japanese state for a dangerous century. She is not some policy wonk tinkering at the margins: She aims to be a transformative figure, one who will restore Japan’s national strength in a world where she believes no one will save Japan but Japan itself. She (accurately) sees Japan as strategically vulnerable: dependent on foreign energy, foreign technology, foreign protection, and falling behind in industrial capacity. Her answer is neither liberal nor conservative in the way we understand those categories today. Her solution is unapologetically statist. She wants to use public spending to pull private money off the sidelines and into her project of national rejuvenation, to rebuild key industries, to expand defense capacity, and to prioritize economic security over fiscal orthodoxy. In Takaichi’s view, Japan’s survival, let alone its flourishing, can only happen through national reinvention, even if it means more debt and institutional confrontation to get there. Japan accomplished this post-Meiji via force. That is likely not an option for Japan today: Meiji 2.0 must be more than martial. To work, it must be a technological revolution, a society that responds to vulnerability not with expansion but with invention.

That’s all quite high-falutin, so let’s get down to brass tacks. Takaichi has, for the moment, solved her domestic political constraints. But that is only level 1 of the video game. The constraints she faces in pulling off this geopolitical revolution are structural. They are not immutable, but to overcome them, things in the Japanese economy will probably have to get worse before they get better. Ultimately, Takaichi wants three things:

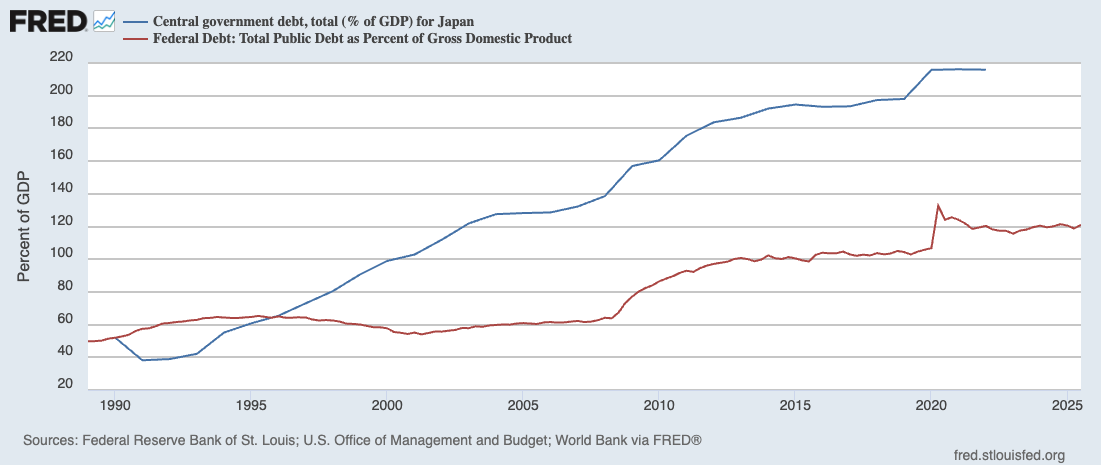

Cheap government borrowing. This is effectively maintaining the status quo. Since the 1990s asset bubble collapse, Japan has lived in a world of low growth, low inflation, and persistent excess savings, the so-called “Lost Decade(s)”. That allowed the Bank of Japan to steadily cut rates to zero, then below zero, and eventually cap long-term yields through yield curve control. For much of the past decade, 10-year Japanese government bond yields hovered around 0% — sometimes even negative. This happened while Japan’s public debt climbed above a whopping 200 percent of GDP. Normally markets would demand higher yields to compensate for that risk. But because most of the debt is domestically held and because most countries in the West maintained low interest rates post-2008 financial crisis, inflation was subdued, and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) was willing to buy large amounts of bonds, borrowing stayed cheap.

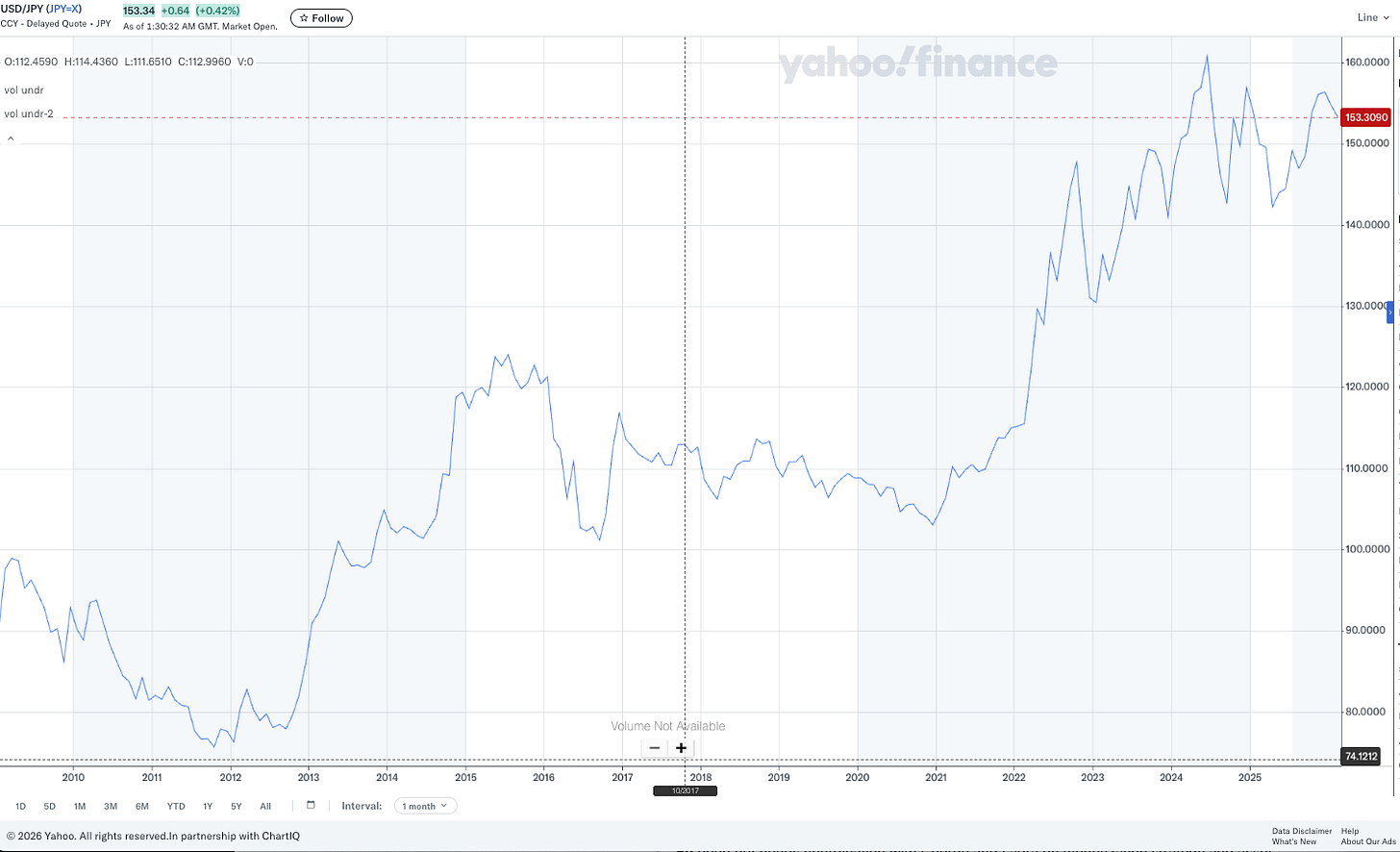

A stable and strong yen. Remember, Japan is a country that imports everything. A weak yen is good for Japanese exporters as it makes Japanese manufactured products more competitive in global markets, but a weak yen also means the purchasing power of the average Japanese citizen declines. In Japan, this is felt more deeply than it is in most countries and magnifies the pain of inflation. In recent years, the yen has been both volatile and weak — and in general has been in a steady weakening trend since 2012. The affordability crisis in Japan is what foiled her predecessors and is what led the electorate to be open to a change candidate with a confident vision of the future like Takaichi.

Higher growth and defense spending. These goals are inextricably linked for Takaichi. They aren’t separate goals, they are the same project. In her worldview, Japan cannot be strategically sovereign if it remains economically stagnant, and it cannot deter China or hedge against U.S. unreliability without materially expanding its defense capacity. Growth funds power; power protects growth. Defense spending, in her conception, isn’t just about security — it’s industrial policy, technology development, and supply chain resilience rolled into one. If Japan doesn’t grow and doesn’t rearm, then all the rhetoric about autonomy is hollow.

And herein lies the rub. She cannot have all three, at least, not in any way I can see. To achieve her vision for Japan, she will have to sacrifice one variable to secure the other two, and then hope that success eventually redeems the one she gave up. She can influence borrowing costs in Japan, but she cannot control the Federal Reserve or global capital flows. She can lean against yen weakness, but only temporarily and at rising cost. And while she can deploy public money toward growth and defense, she cannot command private firms to follow — she has to entice them. Each objective is theoretically attainable. Achieving all of them at once, however, requires threading a needle through forces far larger than any one prime minister. Moreover, aspects of these constraints are beyond her capacity to control.

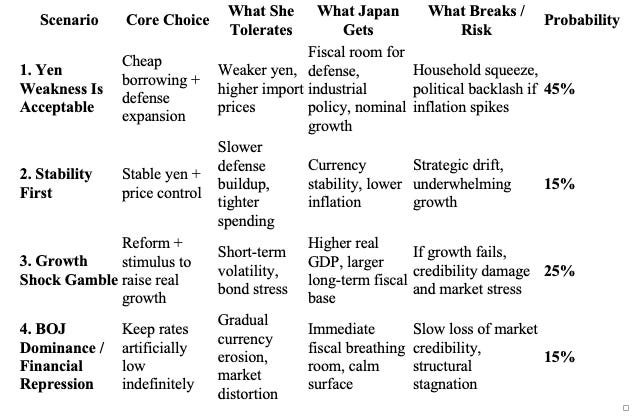

Weighing these balancing forces, I made a little chart with the help of ChatGPT on the potential scenarios going forward for Takaichi. I’ve also ascribed rough probabilities to each scenario. My base case11 is that Takaichi will accept yen weakness to achieve cheap borrowing rates and higher growth/defense spending.

This path will not be easy, but I see it as the most probable because it is the path of least resistance and the one most consistent with success on her own terms. For it to work, cheap borrowing and pro-growth, pro-defense policies must translate into sustained wage gains. Japan’s headline inflation does not look alarming in isolation, but that misses the real constraint. A weaker yen, layered on top of inflation, becomes politically toxic if wages do not rise faster than prices. If purchasing power erodes, the entire strategy begins to unravel.

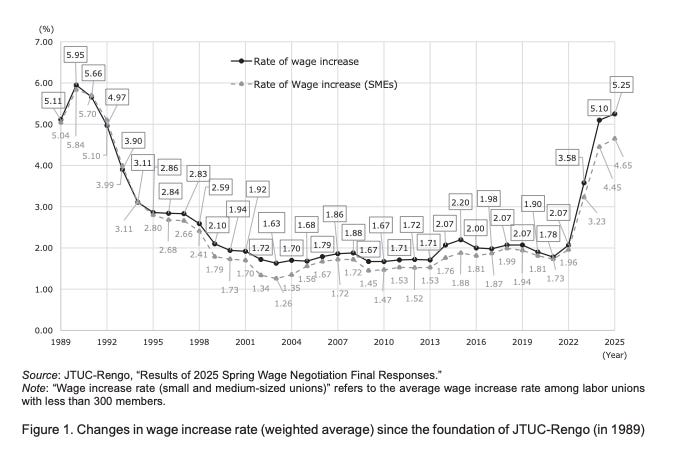

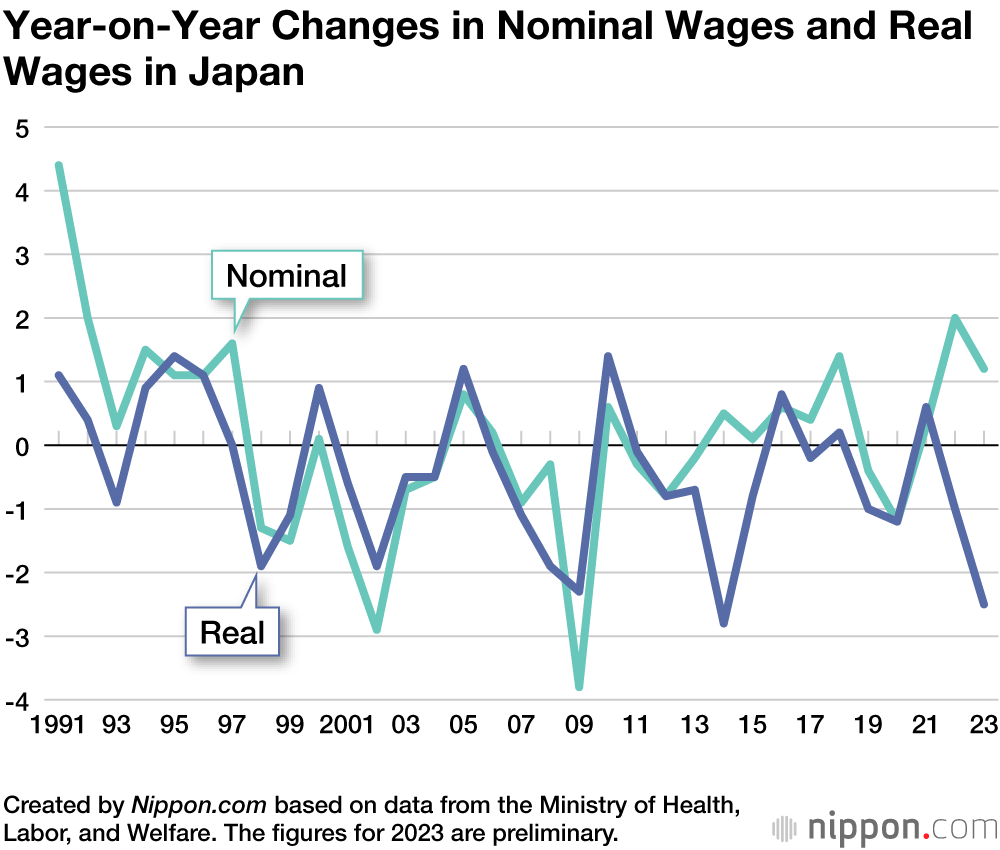

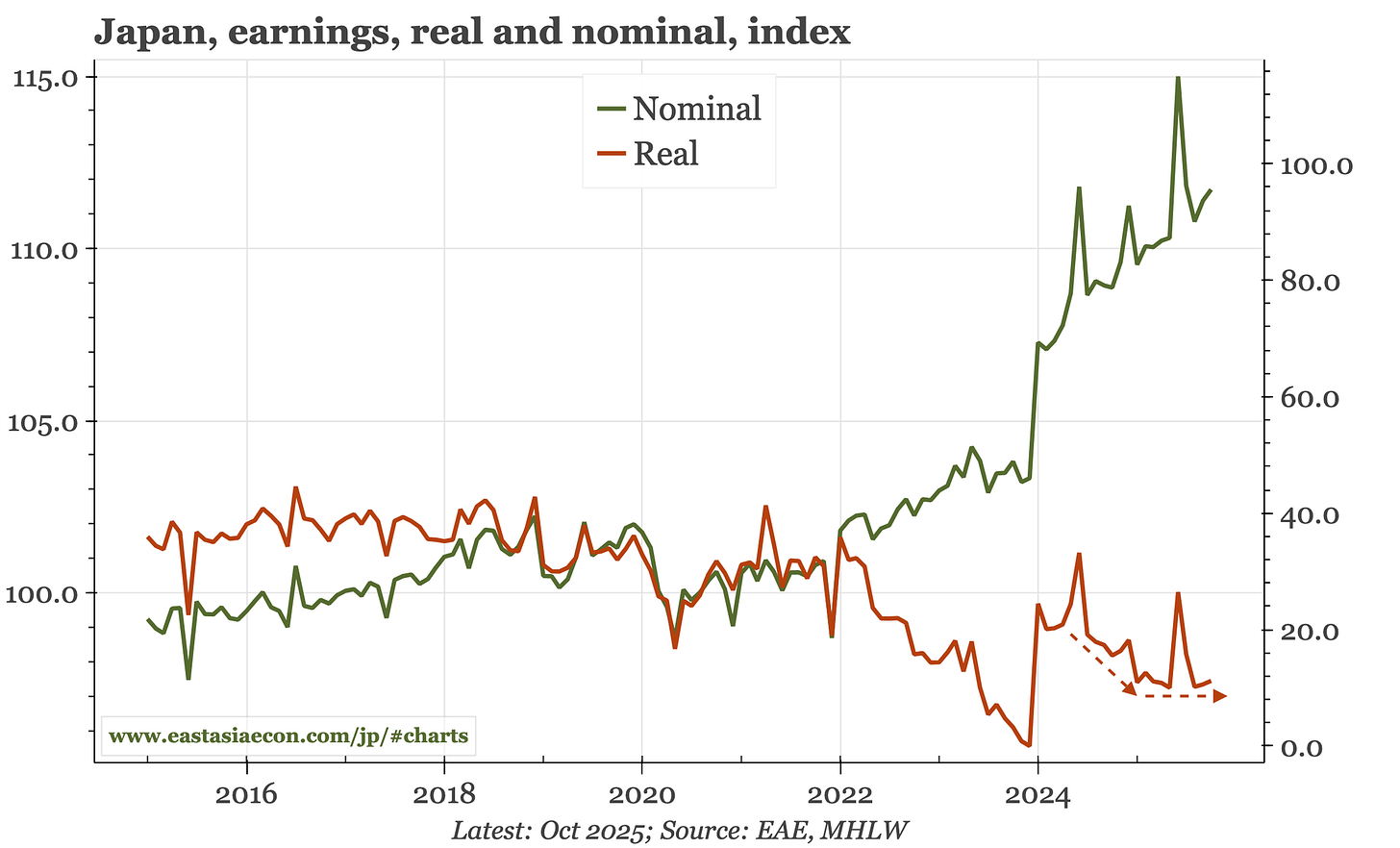

And unfortunately, the erosion of purchasing power is actually what has been happening in Japan. Beginning in 2022, nominal wage increases in Japan started to ascend, and for the last two years, the “Shuntō”, (春闘), literally “spring offensive,” has seen large firms agree to wage hikes above 5 percent. (The “Shuntō” is Japan’s annual spring wage negotiation cycle. Every year, major labor unions coordinate their wage demands and negotiate with employers around February–March. The outcomes set the tone for wage growth across the economy. Even though union membership in Japan is relatively low, Shuntō has outsized signaling power: when large firms agree to 4–5 percent wage hikes, smaller firms often follow, and markets treat the result as a benchmark for national wage momentum.)

Unfortunately, even those hikes have not kept pace with inflation and the weaker yen. Real average earnings have declined steadily since 2021.

If you want to be optimistic, you can make the case that real wages have bottomed out and at least stopped falling (Se below), but that doesn’t change the fact that real wages in Japan declined 1.3 percent in 2025, marking a fourth12 consecutive year of decline, and in fact were down every single month last year.13

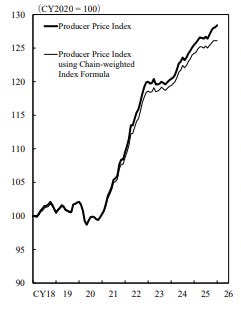

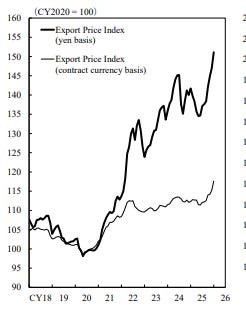

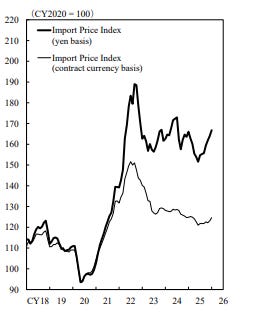

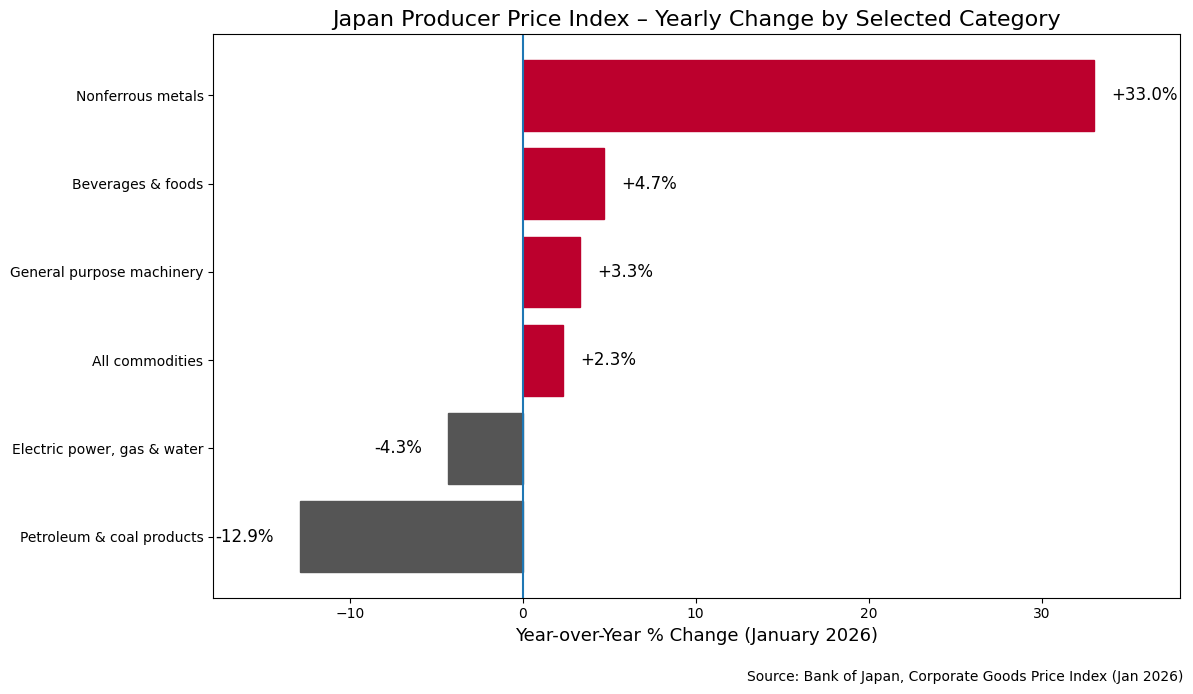

Moreover, the recent trend in inflation is not encouraging. Below are three charts from the latest Bank of Japan release. The first shows the producer price index (2020 = 100). You don’t need to be an economist to see the step change over the past five years — input costs for Japanese producers have climbed meaningfully. Next is the export price index. This is the weak yen doing what a weak yen is supposed to do: boosting the competitiveness of Japanese exports and lifting export prices in yen terms. But the third chart matters more for Takaichi’s political reality: the import price index. Whatever exporters gain from currency weakness is offset — and in some cases overwhelmed — by higher import costs for energy, food, and industrial inputs. Takaichi was not elected by firms benefiting from a favorable currency tailwind; she was elected by households and small businesses feeling the squeeze from rising import prices.

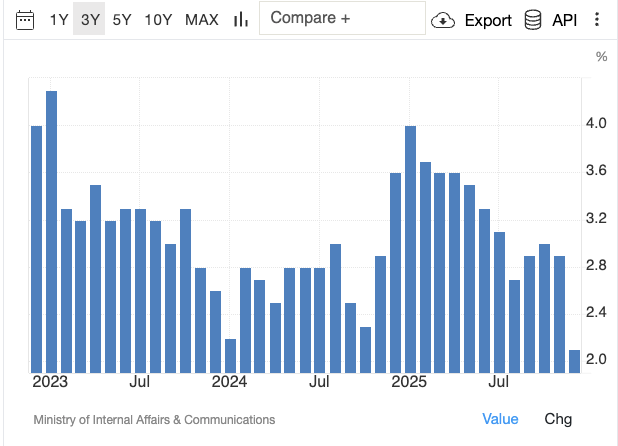

Headline inflation in Japan fell to 2.3 percent in January, but the composition of that number is not especially reassuring. Lower energy prices did most of the work, while industrial inputs, food, and even general-purpose machinery are all running well above that level. In other words, Japan is one geopolitical shock — a U.S.–Iran conflict, for example — away from inflation looking ugly again, and for all of Takaichi’s rhetoric about nuclear energy and self-reliance, this is not a variable she controls. Nuclear currently provides roughly 8–10 percent of Japan’s electricity, down from about 30 percent before Fukushima; even under an aggressive restart scenario, getting back to 20 percent likely takes five to seven years, while returning to 30 percent or higher pushes into a ten-to-fifteen-year horizon. Those ambitions require large capital outlays, cheap borrowing, and sustained policy competence — all of which risk stoking inflation and weakening the yen in the interim. The tools she must use to strengthen Japan could will first intensify the very vulnerabilities she is trying to escape.

All of which brings us to our geopolitical center of gravity: the yen. If my base case is the path Takaichi takes, then the yen becomes the critical signpost for the success or failure of Takaichi’s efforts. Now, keep in mind: the constraint here is not the level of the yen. I can already see the headlines of how the yen has broken the psychological barrier of 160 or 170 on the dollar and how Takaichi is struggling and blah blah blah. The level doesn’t matter. What matters is the rate of depreciation relative to wage growth. The way to monitor this variable is to watch the gap between imported inflation and paychecks.

So again, the question isn’t whether the yen depreciates (it will, in this scenario), what matters is the pace. Is USD/JPY drifting gradually over quarters, or moving 10–15 percent in a few months? The speed matters because businesses and households can adjust to gradual change; they panic at rapid moves. The pace of depreciation then has to be compared directly to nominal wage growth, especially monthly cash earnings data from Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Remember, the key metric here isn’t whether wages are rising (as we saw earlier, they usually are in nominal terms) but whether they are rising faster than imported price pressures. Last but not least, we need to isolate import-driven inflation, particularly food and energy CPI components. A weaker yen hits those first. If food and energy inflation accelerate while wage growth lags, real disposable income contracts…and that’s when political pressure builds and Takaichi’s shine wears off.

In simple terms, that means yen depreciation (year-over-year) minus nominal wage growth (year-over-year) will tell us how Takaichi is doing. If depreciation is (relatively) modest and wage growth outpaces it, the system stabilizes. If depreciation accelerates and wages lag, purchasing power erodes and Takaichi’s industrial strategy starts colliding with household reality.

In other words, what matters is not 160 versus 150. What matters is whether Japanese paychecks can outrun the depreciation of the currency. And that brings us to an uncomfortable place for any geopolitical analyst, because as elegant as the scenario and its signposts may be, what we are really talking about here is belief. Are Takaichi’s approval ratings the reflex of a weary electorate gambling on one last throw of the dice (think Javier Milei in Argentina without the theatrical…eccentricities, shall we call them), or do they reflect something deeper — a willingness to vest authority once again in a state that promises national restoration? In the Meiji era, renewal was sanctified; the emperor was not merely political but divine, and belief in the state carried metaphysical weight. Does a 21st-century democracy still possess that capacity for civic faith, minus the theology (or plus a new theology?) but with the same surrender of doubt? Or is Japan too secular, too aged, too materially cautious for that kind of collective leap — destined not for revival but for dignified management of decline, humming softly along while the demographic clock runs down? Put slightly more tongue-in-cheek…has the rising sun already dipped below the horizon, and all that’s left to Japan is robots to take care of old people and Hello Kitty?

And all of this is before we get to the classical geopolitical question, namely: what does Takaichi mean for Japan’s relationship with China? A few months ago, China tried to punish Takaichi for some fairly mundane commentary about Japan’s strategic interest in Taiwan. Did China simply have a Wolf Warrior relapse? Or was China playing three-dimensional chess and hoping for a Takaichi victory because it would drive a wedge further between Tokyo and Washington (Trump is going to visit Xi four times in 2026, according to him…not Tokyo), and China will be able to deal more pragmatically with even a more remilitarized and wary Japan?

As for Japan, this election was about economics, but it was also about a public that senses China’s rise and feels the ground shifting under the U.S. alliance. Is it quite a Commodore Matthew Perry–level threat…or is it? This is what makes the Meiji comparison all the more apt. Takaichi can do what Abe couldn’t because he was too early. The world has changed, and it is a more dangerous place for Japan than at any time post–World War II. Might Takaichi have known what she was doing all along, and be planning to use China’s inability not to overreact on the Taiwan issue to paper over the economic pain that is coming as she attempts to execute her strategy? I.e., she needs a China boogeyman to pull off her domestic rejuvenation?

And then there is the more uncomfortable possibility: perhaps none of this is chess. Perhaps Beijing misread the moment, and perhaps Takaichi herself is navigating events rather than orchestrating them. If economic pain intensifies and China continues to overreact on Taiwan, that may reinforce her domestic narrative of vulnerability. But whether that’s strategy, coincidence, or simply the structural logic of the region asserting itself is far from clear. Maybe everyone is improvising at the edge of a changing balance of power. Improvisation can lead to misinterpretation, and misinterpretation in East Asia can lead to war.

As you can tell, I have more questions here than answers. But when I am confused about Japan, I always return to something John Toland, author of The Rising Sun: The Decline and Fall of the Japanese Empire, 1936–1945, once wrote about Japanese politics: “Unlike Westerners, who tended to think in terms of black and white, the Japanese had vaguer distinctions, which in international relations often resulted in ‘policies’ and not ‘principles,’ and seemed to Westerners to be conscienceless. Western logic was like a suitcase, defined and limited. Eastern logic was like the furoshiki, the cloth Japanese carry for wrapping objects. It could be large or small according to circumstances and could be folded and put in the pocket when not needed.” Japan can live in a world where China is its economic partner and the U.S. is its security ally without having to pick a side. It is more comfortable with contradictions because it has always had to live with them, rather than with the luxury that overwhelming resource wealth or demographic strength conveys.

But I digress. Tl;dr — watch the rate of the yen’s depreciation to Japan’s wages. Watch if the Finance Ministry and BoJ can stop this train,14 or whether they will be reshaped by a transformative leader. The more likely scenario is Takaichi fails. Structural constraints usually win. But Japan’s previous ascents were never the more likely scenario. And it is very likely that if Takaichi succeeds, she won’t just change Japan’s trajectory — she will reorder assumptions about power, sovereignty, and industrial revival in the 21st century for the world.

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20260209_07/

https://www.nippon.com/en/japan-data/h01758/

https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-japan-thinks-about-energy-security

https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/html/tr/AD0772885/index.html | Japan imports most of its copper, gold, iron, lead, nickel, platinum-group metals, silver, tin, zinc, cadmium, bauxite, nitrates, potash, phosphates, lead, and whatever else it needs.

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/09/elderly-oldest-population-world-japan/#:~:text=Japan%20is%20getting%20ever%20greyer,as%20the%20chart%20below%20shows.

https://geopoliticalfutures.com/midway-moments-waterloo-gettysburg/

As Marius Jansen describes in The Making of Modern Japan, for approximately seven centuries, Japan experienced “warrior rule” – dominated by rival factions. Occasionally strong, centralized figures rose and asserted Japanese power, but for half a millennium, Japan was a “breeding ground for pirates” – a divided island where real power lied with regional commanders and inconsistent patterns of control, landholding, and taxation. At the time of the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan was “one of the modern world’s most fractured polities,” featuring a backwards military and a feudalistic society incapable of banding together long enough to stave of the depredations of foreign powers.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/commentary/2025/11/14/japan/takaichi-and-making-abenomics-20-successful/

Keep in mind these rough probabilities are probabilities for how she will be successful if she is. As for whether she will be…I think the odds are stacked against her, gun to my head, 70-30.

https://english.kyodonews.net/articles/-/70159

https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/japans-real-wages-down-every-month-2025-2026-02-08/