Ode to Vermont's cows

Beauty is truth, truth is cheese. That is all ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

I spoke earlier today at the Vermont Dairy Producers Conference in Burlington, VT. I’d only been to Vermont once before, and that was as a pitstop on the way to a friend’s girlfriend’s cabin in New Hampshire. (I actually remember the trip vividly because we got to this cabin in the middle of nowhere with barely any internet…and Brexit happened the night we got there and I spent most of the evening contorting my body at odd angles to get a single bar of cell service to type out analyst notes and do TV interviews on the surprise news. Also my friend’s girlfriend turned out to be a jerk to whom I had to pretend to be nice the whole time. Anyway, I digress.)

Vermont’s farms produce over 2.5 billion lbs of milk every year. Milk sales account ~65% of Vermont’s agricultural sales and dairy farms operate on roughly half of Vermont’s farmland. Another ~30 percent of Vermont farmland is dedicated to crops grown for dairy feed, so that at end of the day, roughly ~15 percent of Vermont’s land is used for the dairy industry.1 Dairy is part of Vermont’s culture in the same way Mardi Gras is part of New Orleans or peaches are part of Georgia. It is not just the dairy industry that embodies Vermont, but specifically the small dairy farm. Roughly 80 percent of Vermont’s farms have less than 200 cows, which is remarkable considering the average-size dairy farm in the U.S. is ~330 cows.2

As I was preparing my remarks, I realized I didn’t know the answer to an important question, namely, why did Vermont become such an important dairy producing state? Nearby states like New Hampshire, Maine, or even New York don’t have milk in their blood in quite the same way as Vermont. What made Vermont dairy so different?

Being a geopolitical analyst, my first impulse was to study Vermont’s geography, but there was nothing particularly obvious that screamed, “MILK!” Eventually I found an excellent book called The Story of Vermont by Christopher McGrory Klyza and Stephen C. Tromulak. They explained how Vermont did not start as a dairy state at all. Vermont’s first love was sheep — the need for woolen uniforms for U.S. soldiers during the War of 1812 put Vermont on the map.3 (Which just goes to show you that geopolitics literally is at the core of everything — an entire wool industry created because of a war with Great Britain!)

Cows were something of an afterthought. Indeed, “in 1833, Vermont farmers were selling their cows to make room for more sheep.”4 By the latter half of the 19th century, Vermont had also become a prodigious and efficient grower of wheat, corn, and oats. Sheep remained critical to the Vermont farm economy at this time despite the abolition of the wool tariff in 1846 — the need for wool during the Civil War gave Vermont wool a last reprieve, and in 1880, sheep still outnumbered humans in Vermont by over 100,000.5

Beginning in the 1890s, Vermont’s farms entered a quick decline. Between 1990 and 1930, corn production declined 90 percent, buckwheat 88 percent, and oats 60 percent. The sheep population fell from almost 300,000 to a mere 12,000 over the same time period, a veritable sheep holocaust. The reasons for this collapse were not Vermont’s fault, it was out of Vermont’s control. The availability of new, ample farmland in the west, land forcibly and violently cleared of its native populations, made Vermont farmland less attractive. Urbanization and the allure of the modern city enticed young people to leave the family farms, leaving an older generation unable to keep up with the work at a time when farm work was much harder than it is today. Advances in fertilizer drove down the cost of agricultural commodities, while most of the new fancy farm equipment that was invented was better suited for the flat Midwest rather than Vermont’s rolling mountains. Competition from Australian wool and the removal of the wool tariff also hurt.

(Eerie how relevant some of these developments are in light of the challenges facing Vermont farmers today.)

The one exception to the rule was dairy. And this, it turns out, was primarily due to a geographic advantage: Vermont’s proximity to Boston and New York City. These rapidly growing markets were thirsty for milk and other perishable dairy products. Cold storage wasn’t really a thing yet and keeping barns of cows in NYC or Boston would not have worked. Aside from this proximity, from a geographic perspective, there was nothing particularly special about Vermont in terms of favorability towards dairy farming — indeed, “many farms were ill-suited to dairy” — and yet, between 1870-1900, Vermont’s farmers went from making a living through general farming to receiving most of their income through dairy. It was a remarkable, rapid, thorough, and unpredictable transformation.

By the time cold storage came along and enabled Midwestern producers to supply milk to the Northeast, Vermont had already developed a special expertise in the dairy industry, including an early pivot to commercial production of cheese and butter.6 Saint Albans was home to the world’s largest creamery at the time. That meant that even as Vermont dairy farmers lost marketshare in the Northeast…they gained marketshare in other parts of the country because they could transport their milk longer distances. By 1930, over 85 percent of the milk produced in Vermont was shipped outside the state. With this base, Vermont farmers successfully waded into other specialty arenas, like apples and maple sugar. But dairy led the way. Milk was the lifeblood of the state.

Even so, with no unique special advantage conferred by Vermont’s geography, the state’s dominance in dairy began a slow decline after World War II. In 1947, there were more than 11,000 dairy farms in Vermont. Today, there are fewer than 600.7 The average number of cows per farm has almost doubled in the last 10 years, from 150 in 2015 to almost 300 today.8 According to the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food, & Markets, dairy acreage in Vermont has decreased ~37 percent since 2007.9

(An aside — oilseed and grain acreage has increased by 122.1 percent comparison — even in Vermont, the allure of $$ coming from soybean oil for renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel is apparently seductive. I was shocked when one of the first questions I got from the audience was about soybean oil. From a Vermont dairy producer audience! Glad I did the North Dakota Corn and Soybean Expo two weeks ago so I had an answer at the tip of my tongue.)

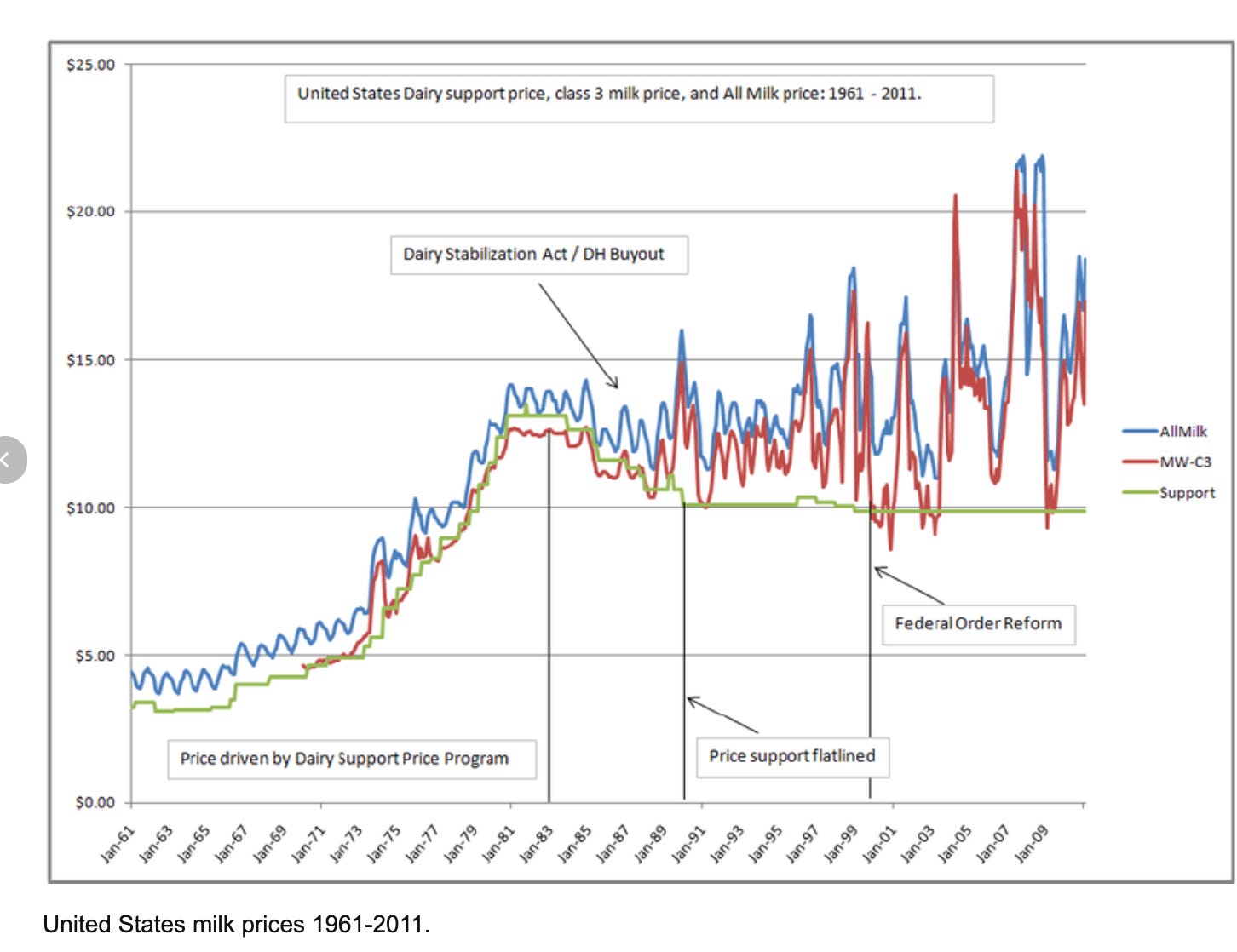

Small-scale Vermont farmers simply cannot compete with larger scale operations — falling per capita milk consumption, a fundamentally oversupplied market, and increases in input costs all conspire to make more dairies unprofitable than not in many states in the U.S., and especially in Vermont.10 As one friend put it to me, dairy farms may generate a lot of economic activity, but unless you can find economies of scale to spread expenses over a larger revenue base, it is not really possible to make a living doing it, certainly not a good one.11 Here’s a few charts that illustrate how challenging it is for dairy farmers nationally — and when you think about what this means for Vermont dairy farmers, keep in mind that their small size is the source of their distinctiveness and is a massive disadvantage in trying to weather these headwinds.

Another aside — I cannot tell you how sad these facts make me after having interacted with the 300+ people at this event. These are people who genuinely love cows. That might sound funny to the majority non-farmers who read my little missives, but they really do love them. I spoke to moms who spend their evenings milking cows and stressing over the loss of calves from previous years. One of the speakers after me gave a fascinating (and graphic) presentation about birthing cows — the crowd listened with rapt attention. Another audience member found me on the stairs after my talk to ask me a few questions and mentioned he’d turned his back on a career in finance…because he just loved raising cows so much.

Armed with the knowledge of why Vermont became a dairy state, I felt comfortable bringing the crux of my message to the audience. In one of my first slides, I shared a few quotes from sources like USDA, U.S. Dairy Export Council, and the National Milk Producers Federation:

“Continued growth of the U.S dairy sector is largely contingent on trade.” – USDA

“While we are not ignoring the U.S. domestic market…exports are essential for dairy farmers across the country.” – U.S. Dairy Export Council

“Exports are critical to the economic viability of U.S. dairy farmers.” – NMPF

“U.S. dairy exporters can compete on quality and price with dairy exporters throughout the world so long as there is a level playing field.” (NMPF)

Supporting exports as a strategy makes perfect sense in a globalizing world. Milk demand in particular is growing faster in global markets than in the United States. Couple that with demographic growth and the quality of U.S. dairy products and you can build a compelling export case. To wit, U.S. dairy exports have slowly crept up to almost 20 percent of total U.S. production since the mid-1990s.

But we don’t live in a globalizing world anymore. We live in a multipolar world where protectionism is the name of the day and where the biggest potential markets for American milk (like, say, India or Indonesia or Mexico) have ambitious plans to be self-sufficient. We also live in a world where the U.S. government is slapping so many new tariffs on different countries and commodities that even I am having a hard time keeping track — and it’s my job to keep track! Doubling down on exports and telling the U.S. dairy farmer that Exports is the Way while President Trump plays “Who wants a tariff?” borders on malpractice.

Moreover, we learned during the 2022 inflation spike and the great 2025 egg crisis that the U.S. consumer, accustomed to cheap food, will pay higher prices. They will moan, wail, and gnash their teeth, but they will. (And if they are like me, they will happily pay a higher price for a better, healthier, more distinctive, and environmentally sustainable product, areas were smaller dairy operations should be able to shine.) Not to mention the fact that the average food insecurity rate in the U.S. is 10.4 percent.12 If the U.S. government is not going to use its immense power to open up new markets for the U.S. dairy farmer, than that farmer has to think in terms of selling his or her product for a higher dollar amount to a population that can pay for it.

I also argued that something seems to be changing in American tastebuds/health choices. How big the change is hard to quantify at this point. The change is big enough that RFK Jr. got confirmed by Congress and there is a whole “Make America Healthy Again” movement that put aside its contempt for Donald Trump during his first term to embrace him wholeheartedly for his second.13 The most relevant example of this for the average dairy farmer is the wild success enjoyed by Fairlife, a Coca-Cola-owned brand of “ultra-filtered milk” — they basically filter out the lactose and the sugar and boost the protein. Coca-Cola agreed to buy out Select Milk Producers’s share of Fairlife in 2020 + performance-based payments through this year. Just look at how those performance-based payments have gone to the moon:

Sounds gross to me…but the consumer loves it, and what do I know about the consumer. Not a whole heckuva lot considering Starbucks, purveyor of the grossest coffee in the history of man, is a billion-dollar company. Whoops, did I get on my Starbucks soap box again? Sorry. Back to Fairlife. Via Bloomberg: Despite being about three-times the price of traditional milk, retail sales of Fairlife topped $1 billion in 2022 — up 1,000% from reportedly $90 million in 2015 when it went nationwide.14 Maybe it’s just a passing craze, but it suggests to me that consumers will pay for well-branded products that scratch some kind of itch. How is it that Coca-Cola has the most successful milk product of the last decade when there are so many small dairy farmers out there who might be able to supply a better and arguably healthier product? Who better to figure out the answer to that question than the basketball mom nursing the calves in the night or the finance bro-turned-cow-caretaker?

I may not understand the Fairlife craze, but one thing I do understand is cheese. Those of you who know me well know the depths of my obsession with cheese. You’ll know I won the lottery if I delete all my social media accounts and retreat to my family home in GA with a few dairy cows and start hawking cheese at local farmers’ markets. Overall U.S. dairy consumption from 1979 to 2019 is flat — but daily cheese consumption has more than doubled during that timeframe.15 The average American eats 40 lbs of cheese per capita. Butter and especially yogurt consumption are also up considerably even as milk consumption continues to plummet. Maybe the best thing that could have ever happened to the Vermont farmer is President Trump and his henchmen deciding Europe sucks — we’ll need someone to step in and provide all the fancy butter and cheese our fromage-obssessed nation demands and currently gets from Ireland and France and Germany and Switzerland.

And if tariffs are used smartly to protect our domestic cheese and dairy industry, then kiss my grits and call me a tariff man too.16 We’ll need Elton John to do a “Tariff Man” cover of “Rocket Man” whilst eating a cheese sandwich stat.

Jokes aside, the overall data for Vermont dairy farms and cows is grim. There is no dancing around that. But I am buoyed by my deeper understanding of Vermont history, and how Vermont has reinvented itself when facing similar situations in the past. Back then, dairy was saving the day from the collapse in other farm products. Perhaps dairy has to die in Vermont for the small Vermont farm to survive, just like the sheep once did, little sacrificial lambs. Or maybe dairy can reinvent itself and take advantage of the opportunities in front of it. Necessity is the mother of invention. Necessity is here. I hope opportunity isn’t far behind.

This data is a little old — from a Middlebury 2017 study — it is the best I could do because the plane I am on does not have Wifi. I also doubt the numbers have changed enough to changed the overall point. https://www.middlebury.edu/college/sites/default/files/2022-04/Holistic.pdf

https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/2024/02/us-dairy-herds-and-policy-and-the-2022-census-of-agriculture.html

https://vermonthistory.org/journal/misc/VermontSheepIndustry.pdf

https://vermonthistory.org/journal/misc/VermontSheepIndustry.pdf

https://vtsheepandgoat.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Story-of-VT-Klyza-Trombulak.pdf

As someone who deeply loves cheese it pained me to read about how we gave up the local know-how and expertise in favor of the cheese and butter that now overwhelms our grocery aisles. But that is a rant for another time.

https://agriculture.vermont.gov/food-safety/milk-dairy

https://www.sevendaysvt.com/food-drink/many-of-vermonts-dairy-farms-have-shuttered-and-the-forecast-is-for-still-fewer-and-much-larger-operations-38341678

https://legislature.vermont.gov/Documents/2024/WorkGroups/House%20Agriculture/Topics%20in%20Agriculture/Dairy/W~Laura%20Ginsburg~Dairy%20Update%20Presentation~4-12-2024.pdf

https://www.sevendaysvt.com/food-drink/many-of-vermonts-dairy-farms-have-shuttered-and-the-forecast-is-for-still-fewer-and-much-larger-operations-38341678

By “good” I mean in financial terms. I know airy farmers love their cows.

As of 2021, I don’t know the latest figure. USDA.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2025-02-10/coke-owned-fairlife-milk-is-soda-giant-s-fastest-growing-brand

https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/charts-of-note/chart-detail?chartId=103984

https://x.com/realDonaldTrump/status/1069970500535902208?lang=en